The Facts in Wax: José María Cano

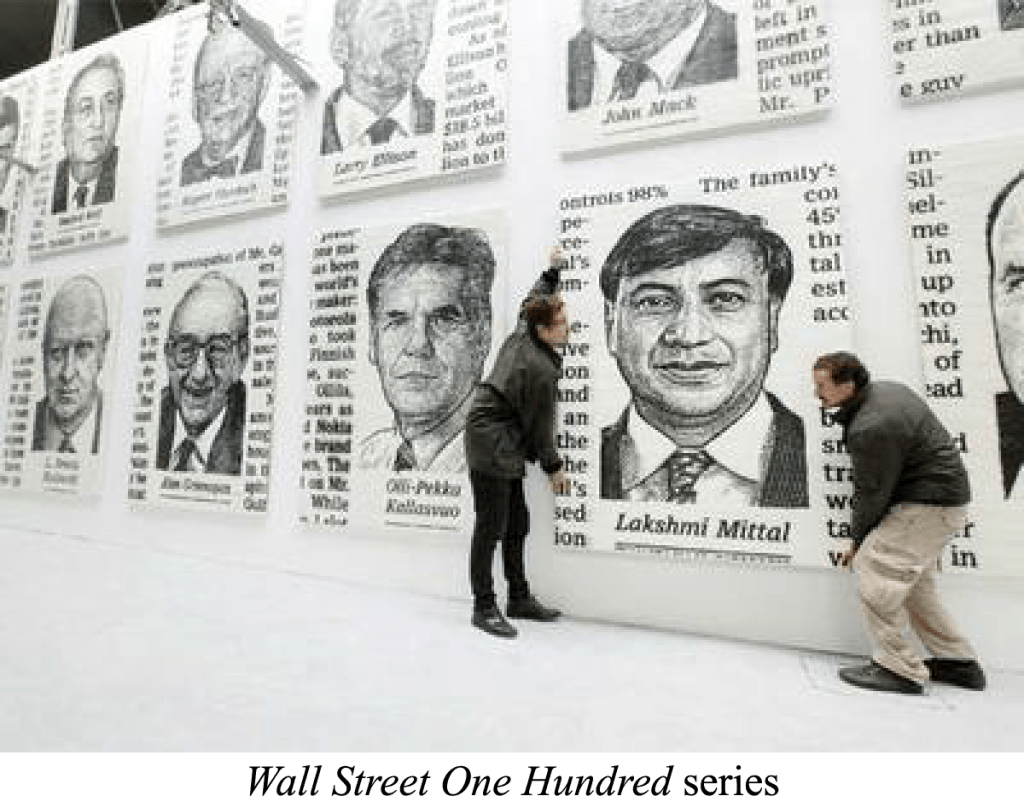

Based on newspaper clippings taken directly from the Wall Street Journal, José María Cano painstakingly reproduced the small portraits, and surrounding the column text in each clipping in large scale using encaustic painting. Wax’s organic origin and its semi-transparent and tactile characteristics contrast with the mechanical and industrial nature of the media used in newspapers. For the artist, there is a close connection between the traditional encaustic procedure and the latest avant-garde technique in terms of themes. Encaustic enables José María Cano to play with binary concepts such as opacity and transparency, the tactile and the optical, and then use these expressive possibilities to exploit their symbolic potential.

Encaustic painting’s genealogy is linked to archaic practices and forms, as well as a belief in the magical power of the image and its creation process. The Fayum mummy portraits made in Egypt in the 1st to the 3rd centuries AD, are early and well-known examples of encaustic paintings. These portraits, painted on wooden panels and attached to mummies, were part of the funerary rites of Roman Egypt. This connection between mummies, death masks, and portrait painting later inspired the French theoretician André Bain to associate the origins of painting and sculpture with what he called a “mummy complex.” He described it as an expression of the psychological need in man to artificially preserve his bodily appearance.[1]

Encaustic painting’s genealogy is linked to archaic practices and forms, as well as a belief in the magical power of the image and its creation process. The Fayum mummy portraits made in Egypt in the 1st to the 3rd centuries AD, are early and well-known examples of encaustic paintings. These portraits, painted on wooden panels and attached to mummies, were part of the funerary rites of Roman Egypt. This connection between mummies, death masks, and portrait painting later inspired the French theoretician André Bain to associate the origins of painting and sculpture with what he called a “mummy complex.” He described it as an expression of the psychological need in man to artificially preserve his bodily appearance.[1]

Research has found that only about 1-2% of Fayum’s people could afford to have their portrait painted, and that sitters typically belonged to the affluent upper social strata of government officials, religious dignitaries, military officers and other well-connected families.[2] Therefore, Cano’s artwork includes are contemporaneous portraits of people whose (economic) legacies have become relevant worldwide, implying both historical and physical references: the typical portraits of great businessmen of the world like chairmen and directors of transnational companies, banks, public treasuries, ministers and other personalities of economic power who appear in every new item in the Wall Street Journal, along with a small extract from the text of the item. The Wall Street One Hundred series reveals elements of fetish and funereal portraiture that are especially apparent in a large spatial installation. As a result, this series is reminiscent of both necropolis and wax works, evoking the notion of sacred and contemporary icons. The portrayed financiers represent the idols of a society that sees capital and economic growth as sacred values.

Cano’s portraits of super-capitalists in his Wall Street One Hundred series may be thought of as an archive rather than a few discrete portraits that happen to bear a similar formal layout. The textual area in Cano’s newspaper paintings acts as a frame for the image. This framing adds intensity to the pictorial image, acting like a series of brackets or quotation marks, hemming in the portrait head, to make the viewer see these already public portraits under a new, critical and analytical light. In the painting, the coldness and transitory character of the newspaper item becomes something perpetual, decorous, and elegant.

By making paintings of the richest and most powerful capitalists -people whose money is as much behind and involved with the artwork as it is in other forms of commercial exploitation- Cano is also placing the normally hidden dealings of the art world at center stage. Portraits of people like Alan Greenspan and Vladimir Putin denounce the capitalist face of contemporary society and at the same time, criticize the way some artists deliberately embellish perversity. In fact, Cano’s artwork alludes to the filter that the art world uses to sift and hide reality; it is both the cause and theme of its own existence.

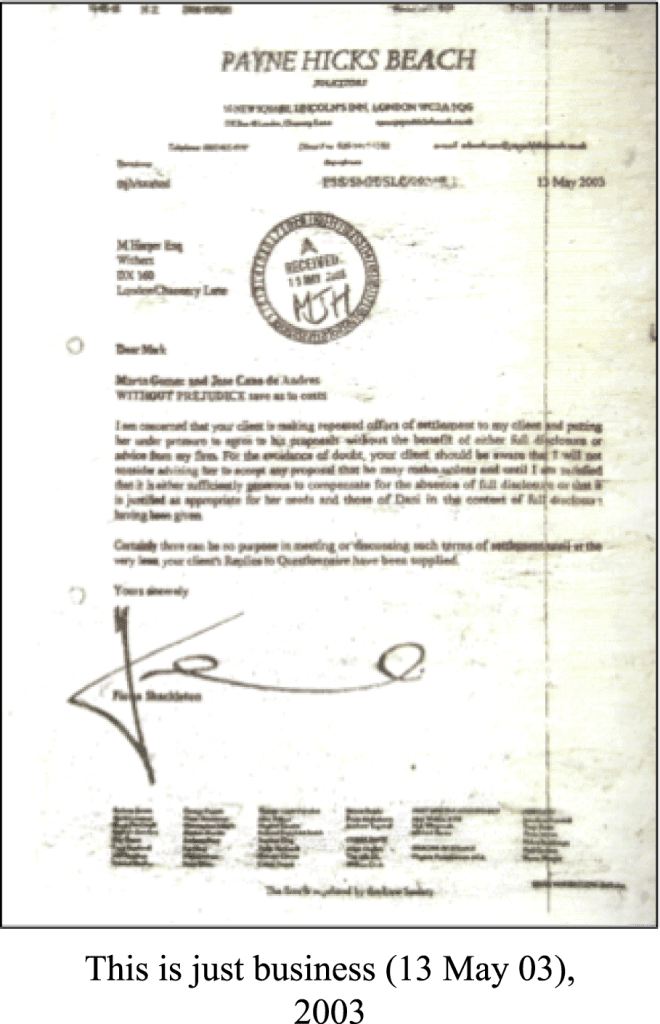

Cano’s ideology is inspired by painter Joaquín Torres García, who said, “Reality has three dimensions, whilst truth has only two.”[3] This statement has been depicted since his first series of paintings, which were meticulous copies of his own divorce papers. Each printed document of the divorce procedures was enlarged and transformed into a waxed canvas, just like some penitence or catharsis: “Friends were asking me, ‘Why are you doing this?’ It was taking hours. But it was great. I was finding in painting my way out”.[4] At precisely the same time Cano began making paintings that were meticulous copies of drawings made by his young son Daniel, who has Asperger’s Syndrome.

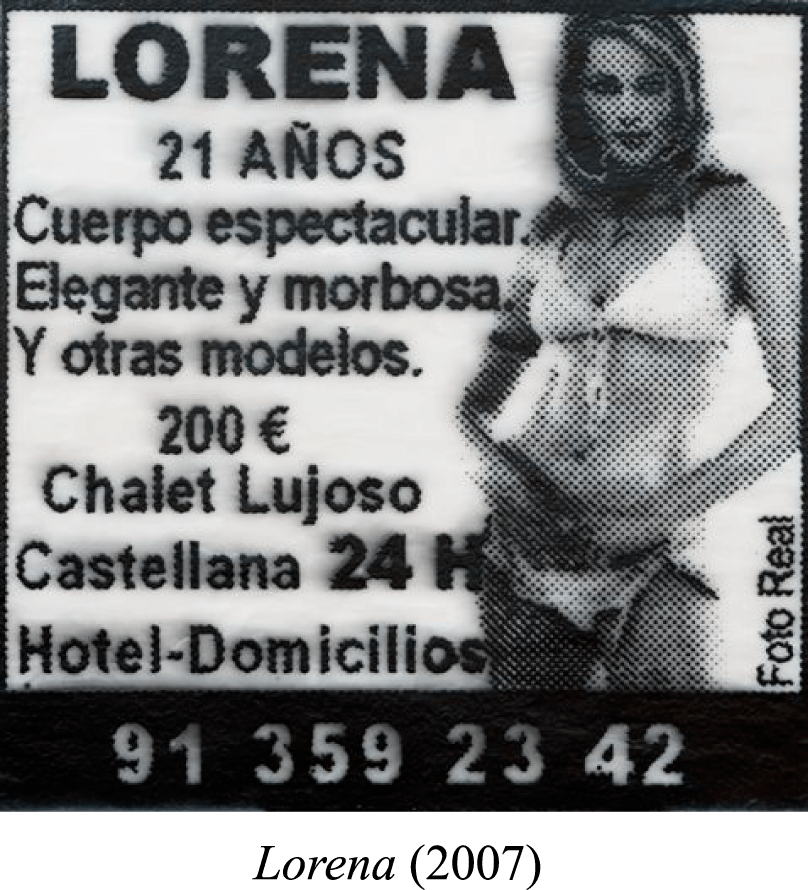

His work does not show an abstract reality, nor does it portray the problems or shortcomings of society today: it is a warning, a lighthouse, and advertisement for something that is real, happening despite the world. Although everyone criticizes it, everyone takes part in the masquerade. In his series Why Rent When You Can Buy?, Cano seeks to present art and prostitution within the same idiom of consumption and projection. Derived from small ads for escorts, Cano reproduces these generic mass-produced portraits in wax in an attempt to create authentic monuments with a three-dimensional effect. In the artwork Lorena, her toned body announces itself in pixelated perfection announces itself: “Lorena, 21 años. Cuerpo spectacular. Elegante y morbosa. Y otras modelos. 200 €. Chalet Lujoso Castellana 24H Hotel-Domicilios.” Between these lines lies the fertile ground of necessary fantasy that enables the passage from the symbolic to the real. Rendered entirely in black and white encaustic, Lorena is not herself, nor is she the delicate and minuscule newspaper advertisement from which her image is derived. She is the work of the artist José María Cano: a denuded icon to the prostitution of art. “Art is like sex,” says Cano. “When you have sex with someone, you believe that you possess that person. When you buy art, as well, you believe that you possess something.”[5] In fact, they are not products of innate and absolute value. The consumption of art, like the consumption of another individual for sexual pleasure, is about the image, and the visual manifestations of fetishism.

His work does not show an abstract reality, nor does it portray the problems or shortcomings of society today: it is a warning, a lighthouse, and advertisement for something that is real, happening despite the world. Although everyone criticizes it, everyone takes part in the masquerade. In his series Why Rent When You Can Buy?, Cano seeks to present art and prostitution within the same idiom of consumption and projection. Derived from small ads for escorts, Cano reproduces these generic mass-produced portraits in wax in an attempt to create authentic monuments with a three-dimensional effect. In the artwork Lorena, her toned body announces itself in pixelated perfection announces itself: “Lorena, 21 años. Cuerpo spectacular. Elegante y morbosa. Y otras modelos. 200 €. Chalet Lujoso Castellana 24H Hotel-Domicilios.” Between these lines lies the fertile ground of necessary fantasy that enables the passage from the symbolic to the real. Rendered entirely in black and white encaustic, Lorena is not herself, nor is she the delicate and minuscule newspaper advertisement from which her image is derived. She is the work of the artist José María Cano: a denuded icon to the prostitution of art. “Art is like sex,” says Cano. “When you have sex with someone, you believe that you possess that person. When you buy art, as well, you believe that you possess something.”[5] In fact, they are not products of innate and absolute value. The consumption of art, like the consumption of another individual for sexual pleasure, is about the image, and the visual manifestations of fetishism.

According to context and circumstances, Cano’s paintings can function alternatively as fetishes, idols, and totems, which to some extent explains the enigmatic character of his works. The surfaces have a rich physicality. There is something peculiar to wax; perhaps it has to do with its perceived firmness and simultaneous delicacy. Cano’s images seem at once spontaneous and at the same time, they give the impression to be carved in marble. Wax’s malleability defines the ambiguous status of the medium between the transient and the permanent.

According to context and circumstances, Cano’s paintings can function alternatively as fetishes, idols, and totems, which to some extent explains the enigmatic character of his works. The surfaces have a rich physicality. There is something peculiar to wax; perhaps it has to do with its perceived firmness and simultaneous delicacy. Cano’s images seem at once spontaneous and at the same time, they give the impression to be carved in marble. Wax’s malleability defines the ambiguous status of the medium between the transient and the permanent.

José María Cano’s artworks have been presented in at the National Museum of Modern Arts, Tokyo (2014), in the Pallazo delle Arti Napoli (2013), in the 54th Venice Biennale (2011), in Sotheby’s “God Sell the Queen”, (2009), in the Moscow World Fine Art Fair (2008), in the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2006), and ARCO 06 (2006), among others.

[1] Bazin, André. “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” Faculty of Georgetown. Trans. Hugh Gray. Summer 1960. Web. 26 Feb. 2016. <http://faculty.georgetown.edu/irvinem/theory/Bazin-Ontology-Photographic-Image.pdf>. p. 4 and 5.

[2] “Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt.” Met Museum. 15 Feb. 2000. Web. 26 Feb. 2016. <http://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-museum/press-room/exhibitions/2000/ancient-faces-mummy-portraits-from-roman-egypt>.

[3]“José-María Cano Biography.” Kristy Stubbs Gallery. Web. 26 Feb. 2016. <http://www.stubbsgallery.com/artists/38-jos-mara-cano/biography/>.

[4] Cano, Jose María, and Fernando Frances. Jose-Maria Cano: Materialismo-matérico. Málaga: CAC Málaga, Centro De Arte Contemporáneo Málaga, 2007. p.287

[5] Cano, José María, Jaroslav Anděl, Brooke Lynn. McGowan, and Peter Suchin. José-María Cano: Welcome to Capitalism! = Vítejte v Kapitalismu!:. Prague: Dox Centre for Contemporary Art, 2008. p.93