New Hampshire is especially rich in its diversity of birds. It’s estimated that some 300 species of birds regularly flap their wings through New Hampshire, including nearly 200 species of songbird, one of which – the purple finch – has been the state bird since 1957.

Quieter forests are cause for concern as conservationists see decreasing populations and diversity of songbirds in New England, many of which call New Hampshire home. NASA satellite data helped map the changing forest landscape, better equipping land managers to react to the effects of forest fragmentation and changing songbird populations. And that’s music to conservationists’ ears.

Conservationists are increasingly concerned, however, about the abundance and diversity of New England songbirds. Recent research and field studies have shown a marked trend towards decreasing populations of passerine birds – also known as perching birds or songbirds. Changes in passerine abundance and distribution are often indicative of underlying changes in their environment, such as habitat loss, climate change, and an increase of predatory species.

In a joint project with the National Audubon Society, NASA DEVELOP brought Earth observations into the equation to help map and model the changing suitability of New England’s landscape. NASA Earth Applied Sciences’s DEVELOP program spearheads research partnerships seeking solutions to environmental and other Earth science issues.

“[With Earth-observing data] we now know how [forest] fragmentation affects the likelihood of a bird occupying, colonizing, and abandoning a habitat.”

–Kiersten Newtoff, NASA DEVELOP

One issue for New Hampshire’s songbirds is the increasingly patchy nature of their habitat. The Audubon Society lists forest fragmentation and habitat loss – due to stressors such as commercial development and climate change – as a leading threat to forest birds in the Northeast. Forest fragmentation occurs when a tree-filled habitat gets cut down into smaller, more solitary patches, often with open lands or human development running between them.

“While habitat occurs gradually in nature, habitat destruction by humans is increasing fragmentation to an alarming degree,” said Sam Weber, DEVELOP team member. “More houses and highways … mean less forest and more fragmentation.” More fragmentation also leads to more “edge” environments – pronounced boundaries between different habitats.

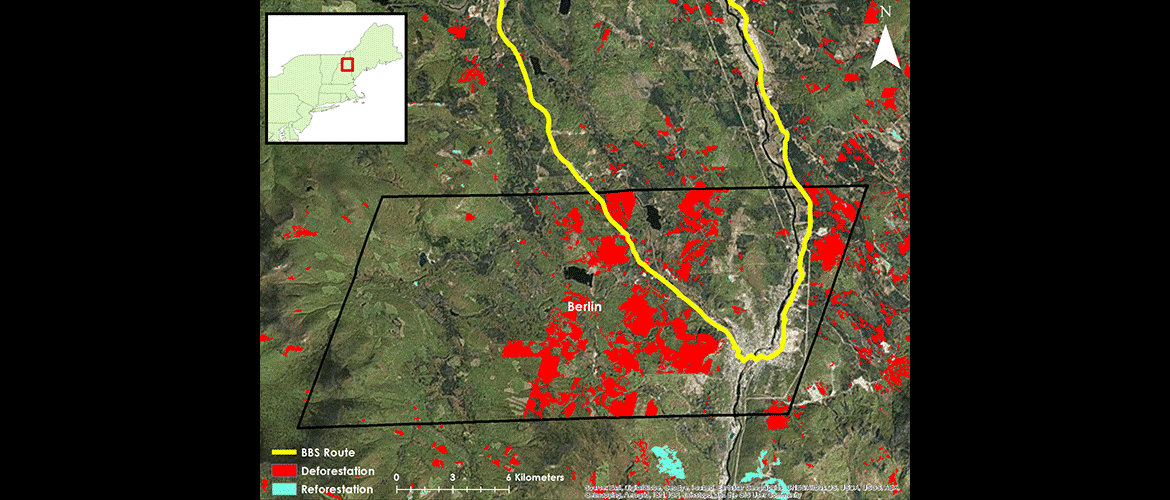

The project team reviewed satellite and sensor data to view forest fragmentation, landscape features, and vegetation across New England. With this information, the team identified highly fragmented forests and the health and density of the forest cover.

Next, the DEVELOP team needed to know the location of New England’s songbirds, so it used the North American Breeding Bird Survey, a partnership between the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and Canadian Wildlife Service. The survey provides long-term, large-scale population data for breeding bird species, and it has observed declining trends in songbirds.

“We found that songbirds with different life histories have different responses to forest fragmentation. Edge-dwelling songbirds appear to have left habitats as [dense vegetation] increased and patch area decreased,” explained DEVELOP team member Kiersten Newtoff.

“However, forest-dwelling species left habitats with increasing edge. And birds living in grasslands, as expected, left areas with increasing forest cover.”

With this discovery, she added, “we now know how fragmentation affects the likelihood of a bird occupying, colonizing, and abandoning a habitat.”

When the project concluded in 2014, the team handed its data over to the National Audubon Society, which incorporated the model output into its strategies for land conservation and management.

“Having received our results and end products, our project partners are now better equipped to react to the effects of forest fragmentation and changing songbird populations,” Weber said. “Each songbird has a slightly different habitat preference, so wildlife managers can use this model to create customized conservation plans based on their species of choice.”

For the purple finch, which has seen a 52% cumulative decline during the last 50 years of the Breeding Bird Survey, this DEVELOP project provides some guidance – and hope. With strategic conservation, the purple finch can continue singing the praises of New Hampshire for many years to come.

This story is part of our Space for U.S. collection. To learn how NASA data are being used in your state, please visit nasa.gov/spaceforus.