Francois Truffaut’s first film, The 400 Blows, featured a young actor named Jean-Pierre Leaud as Antoine Doinel, a 14-year-old boy who seeks to escape his horrible family life. The end of the movie is a freeze-frame of Antoine, as he reaches the sea, but faces uncertainty in his life ahead.

Francois Truffaut’s first film, The 400 Blows, featured a young actor named Jean-Pierre Leaud as Antoine Doinel, a 14-year-old boy who seeks to escape his horrible family life. The end of the movie is a freeze-frame of Antoine, as he reaches the sea, but faces uncertainty in his life ahead.

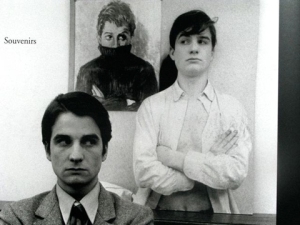

Despite that ending, Truffaut and Leaud would continue the story of Antoine, through one short film and three features, in all covering 20 years. It is the longest association of director, actor, and character in movie history.

Truffaut returned to Antoine in 1962 when he was asked to make part of an omnibus film. The result was Antoine and Collette (called Love at 20 in France), a look at Antoine living on his own and trying to romance a young woman (Marie-France Pisier), who kind of strings him along. It would mark a habit of Antoine’s–he would fall in love with a girl’s whole family, making up for the loveless home he grew up in.

The second feature was Stolen Kisses, released in 1968. Much more comic in tone than The 400 Blows, the film views Antoine after being kicked out of the army, struggling to find himself in a series of jobs.

This film is really a confection, not very substantial but with a lot of Gallic charm. This, even though it was filmed during the turmoil surrounding the dismissal of Henri Langlois from the Cinematheque Francais, which caused riots in Paris. The film is dedicated to Langlois, and during the opening credits we see the closed doors of the Cinematheque.

But Truffaut was not an overtly political filmmaker. 1968 was one of the most turbulent years in world history, especially in France, but there’s hardly a whiff of it here. The only direct mention is when Antoine’s girlfriend (Claude Jade) mentions she has been to a demonstration, and he reacts as if she said she went to the moon. Truffaut was a sentimentalist, and this is a delightful but insubstantial romantic comedy.

The opening scenes show Antoine being unceremoniously and dishonorably discharged from the army. He makes faces as his commanding officer dresses him down, reminding him he will be unable to get a civil service job, suggesting he may sell neckties on the street. Recalling Antoine’s urge to roam from The 400 Blows, we hear how often he went AWOL.

As with Antoine and Collette, Antoine’s only family is the parents of his girlfriend. This time she’s Christine, whom he wrote to in the army, but they seem to have settled into a friendship. Christine’s father gets him a job as a night clerk at a hotel, but he gets fired when a private detective tricks him into opening a door to reveal a woman in the midst of adultery. The detective (pointedly name Henri) feels bad for him and gets him a job at his detective agency, where Antoine becomes the most hapless detective outside of Inspector Clouseau.

One of his assignments is to go undercover at a shoe store, to find out why the owner (Michel Lonsdale) is so disliked. He ends up falling for the man’s wife, and, similarly to The Graduate, which came the year before, the two engage in an affair in which Antoine is bumblingly nervous, while the wife (Delphine Seyrig) is assured.

This film is like The Graduate in many ways, as it captures the uncertain time of a young man who doesn’t quite know where he fits in. As with The Graduate, politics are of no interest to the young man–he’s a misfit, not a revolutionary.

The third feature in the cycle was Bed and Board, from 1970. It is an absolutely delightful picture that made me laugh several times, and I always had a smile on my face. In some ways it is proto-Woody Allen romantic comedy.

Antoine is now married, to Christine. They live in a tight-knit apartment building, where a number of endearing oddballs live, such as the man who won’t leave his apartment until Marshall Petain dies.

Antoine and Christine are happy, though poor. She teaches violin lessons. He starts by working in a flower shop, trying to revolutionize a method of dying flowers. That doesn’t work, so he ends up at a hydraulics company, steering miniature boats in a small-scale harbor. They have a baby son, and there’s some comedy about what his name is. Christine wants Ghislain, but Antoine says that sounds like a baby who wears velvet knickers. He wants Alphonse, but Christine thinks that sounds like a peasant. Since Antoine fills out the paperwork, Alphonse it is.

It is at his new job that Antoine meets a Japanese woman, Kyoko (Hiroko Berghauer). The two enter an affair, though Antoine is quickly tired of it, as he has trouble sitting at those low Japanese tables and the two have nothing to talk about. Christine finds out about it (in a lovely scene involving opening flower petals) and kicks him out. Will true love conquer all?

Truffaut, as with Stolen Kisses, films this as a meringue, not getting heavy but just following his characters as they bounce through the pinball machine. There are a lot of little quirks and eddies, such as when an old policeman says of Christine, “I wouldn’t lay her well, but I would lay her often.” Jacques Tati makes a cameo, in full Monsieur Hulot costume. There’s a running gag involving a fellow who owes money to Antoine, but every time they run into each other, Antoine is owed even more money. And there’s a recurring appearance by a guy everyone calls “the Strangler” who turns out to be a TV comedian.

But the heart of the film is the buoyant and funny relationship between Antoine and Christine. If indeed Antoine is part Truffaut, there appears to be self-satirization, such as when Christine says of Antoine’s biographical novel, “I don’t like this business of writing about your childhood, dragging your parents through the mud. I don’t know much, but one thing I do know – if you use art to settle accounts, it’s no longer art.” Antoine, who again is friendly with Christine’s parents (he has a pleasant run-in with her father at a whorehouse) says, “I like all parents. Except my own.”

Though the film could be seen as Truffaut’s Scenes From a Marriage, it never gets very serious. Christine never really gets that mad at him, and there’s always a sense that they will get back together. The film was intended to be the last in series, but ten years later Truffaut and Leaud teamed up one more time.

That film was Love on the Run, from 1979. Truffaut said he was dissatisfied with the film, and though it has a certain charm, he was right. The film ends up being a summation of the films before, and doesn’t offer any new insights into the character. As Truffaut pointed out, Antoine never evolves.

The film starts on the day of Antoine’s divorce from Christine. They have amicably split, but Jade has had enough of his affairs and self-centeredness. Antoine is now living with a record-shop employee, Sabine (Dorothee). But when he runs into his old girlfriend, Colette (again Marie-France Pisier) he impulsively hops on a train with her. She has been reading his book, a barely fictional account of his life, which has been told in the four previous Doinel films.

The double-edged sword here is that Truffaut was able to use film clips from those films. When Antoine remembers something, we can see a film clip of it, as when he lies about his mother dying in The 400 Blows, or when he has an affair with the Japanese woman in Bed and Board. But having seen all those films in the last few days, it has the effect of being a highlight reel, not a real movie. Antoine is still self-centered–Pisier tells him so–and his relationship with Sabine is based on a serendipitous, albeit romantic, coincidence.

The one spark here is that Pisier, who co-wrote the script, gives herself a subplot involving her defending a child murderer. Though I appreciate the attempt to give one of Antoine’s woman a life beyond him, it sticks out like a sore thumb.

It’s a shame the series ended on such a flat note. There are some touching scenes, such as when Antoine visits his mother’s grave for the first time (she’s buried next to the woman who inspired Camille). The closing credits are intercut with scenes of young Antoine from The 400 Blows, laughing as he spins around in a carousel. That’s moving, but could have meant so much more with a stronger film.

Leaud, who also made many films with Jean-Luc Godard, was an interesting actor in these films. Of course he was mesmerizing in The 400 Blows, but in the other films he’s a loose-limbed, comic actor, gliding through each film as if he were on roller skates, trying his best to stay out of trouble but failing utterly. He still makes films today, but nothing with the impact that his Doinel films did.

Truffaut definitively stated that Love on the Run was the last Doinel picture. Sadly, he died in 1984, so there was no chance to go back on that proclamation. As a package, they are an interesting portrait of an artist covering a character through history, which has been done often in literature (as John Updike did with Rabbit, or Richard Ford with Frank Bascombe), but usually a director doesn’t have the luxury of using the same actors. Truffaut did, and we are all the beneficiaries.