In the present, coming-of-age films are commonplace and represent a well-established genre of filmmaking. Films such as Stand by Me (1986), Mean Girls (2004) and Napoleon Dynamite (2004) are practically folkloric, fitting the tropes of this popular “indie” cinema. However, one singular metteur-en-scène set the trend for this style of filmmaking long before it had become an established genre. The man was French New Wave filmmaker, Francois Truffaut, and the films were his so-called “Antoine Doinel cycle”.

For the uninitiated, the French New Wave or Nouvelle Vague was a cinematic movement in the late 1950s and 1960s in which young, budding French filmmakers rejected the staid cinéma de qualité (so-called “Quality Cinema”) which, many argue, was comprised mainly of unimaginative “filmed theatre” techniques. In opposition to this, they created a cinema with the objective of achieving a degree of realism through techniques such as the use of non-professional actors, natural lighting, exterior shooting, and improvised dialogue.

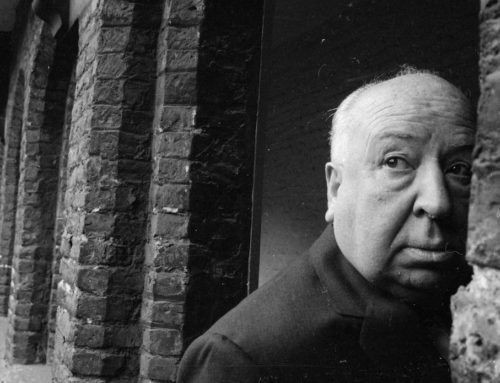

Francois Truffaut, born in 1932, was a young Parisian and the product of a loveless marriage, who sought refuge from his miserable life, in the cinema. Going to the pictures represented a clandestine pleasure for Truffaut, who would often sneak in, underage, without paying, and without the knowledge of his parents. Truffaut would obsessively watch films over and over again to the point of being able to recite their dialogues by heart. This passion took a hold of him and he and other cinephiles formed their own film club screenings, at which Truffaut had the fortune of meeting people like André Bazin, renowned film critic at the helm of the film publication, Cahiers du Cinéma (which, of course, still exists today).

Later on, Truffaut was to have one of several personal setbacks – he joined the army in Post-War France after which he was promptly arrested for desertion. Fortunately, Bazin was able to bail him out after persuading the authorities that Truffaut was basically a good natured person but he had become unbalanced. After Truffaut’s brush with the law, Bazin integrated Truffaut into the writers team at Cahiers. Truffaut showed real promise and while there he also met another budding filmmaker who was later to become his sworn enemy, the infamous Jean-Luc Godard (“une merde”, as Truffaut would later famously describe him….).

Truffaut had his big filmmaking break in 1959 when he burst onto the Cannes Film Festival with his film, Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows), a film about young Parisian boy, Antoine Doinel, and the trials and tribulations of growing up in a loveless family before making the decision to try and make it on his own. Doinel is portrayed by French cinema icon, Jean-Pierre Leaud. It is well documented that both he and Truffaut had strong working and social relationships. Their closeness and their facial similarities led many to confuse both director, actor, and character. Truffaut once humorously commented on this funny mélange that he and Léaud produced, as well as the fact that this tripartite relationship appropriately lends itself to the highly autobiographical aspects of his cinematic work.

In his portrayal of Doinel, Léaud became something of a poster boy for displaced youth before the 1960s and youth culture got into full swing (if you’ll pardon the pun). Who could forget the final scene in which Doinel tries to escape from a Youth Detention Centre, only to be fettered by the sea. He breaks the fourth wall, looking at us helplessly as the camera zooms in and immortalises his image in freeze frame. Truffaut followed shortly after with his second Doinel chapter, Antoine et Colette (Antoine and Colette), a short segment which formed part of the collective film, L’amour à vingt ans (Love At Twenty, 1962), the handiwork of several budding film directors. In this film, Doinel is living an independent existence as a young adult, working in a Phillips record factory and desperately trying to court Colette (Marie-France Pisier) whom he spies at a classical music concert. Unfortunately for Doinel, the love goes unrequited and by the time we get to Baisers Volés (Stolen Kisses, 1968), Doinel is in his twenties, still jobbing, trying his hand at employment as diverse as hotel night porter and private detective. However, this time he has his eyes set on Christine Darbon (Claude Jade) and we follow the ups and downs of their relationship.

Feeling almost like a continuation of that same film, Domicile Conjugal (Bed And Board, 1970) charts the unfortunate breakdown of Christine and Doinel’s relationship, with their young son, Alphonse, in the middle of it all. Meanwhile, Doinel starts working for an eccentric American inventor and, while at work, is struck by the exotic kimono-clad figure of the Japanese girl, Kyoko (Hiroko Berghauer). Despite his best intentions, oriental practices appear too much for him (he even struggles to sit-cross legged on the floor to eat with her) and they cannot break down the language barrier. With their relationship literally lost in translation, Antoine seeks the familiar advice of Christine, for whom he now has something resembling a brotherly affection.

The final chapter, L’amour en fuite (Love On The Run, 1979) witnesses the irremediable breakdown of Doinel and Christine’s relationship as they file for divorce and share custody of Alphonse. Antoine’s roving eyes are now set on Sabine (Dorothée), an employee of a record shop. During their relationship, Antoine has a chance encounter with his old flame, Colette (Pisier), on a train. They discuss the autobiography he has published which has a particular focus on his romantic relationships, and compare notes on their own shared past. As chance would have it, all of Doinel’s lovers become acquainted in this film like some day of judgement in which they all discuss his haplessness in matters of love. In the end, Antoine and Sabine, who have, equally, had their ups and downs, reconcile themselves to the fact that they have no idea where life will take their relationship, but that not knowing is half the fun in this game of life. In the final sequence, the camera pans queasily from left to right, as we get a jump cut to the famous shot from the debut film, Les Quatre Cents Coups, in which Doinel is a boy is spinning in the rotating fairground ride which, as many have commented, takes on the image of the zoetrope, a primitive form of filmmaking and, therefore, the metaphor of cinema itself. The headiness of life and, indeed, of cinema, come together as one.

‘The Growing Pains of Antoine Doinel’ is an article written by Matthew Bruce. You can find out more about Matthew on his site.