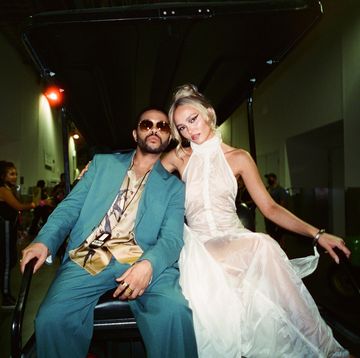

Carl Cox waited for his time. It was shortly before one-thirty on a Saturday morning in late September. Wearing a black T-shirt, black-framed glasses, and black jeans, he stood at the side of the stage in the Mayfield Depot in Manchester — a vast, disused rail terminal in the heart of the city that has become a thrilling entertainment venue, and the home of The Warehouse Project club nights. Cox listened as Peggy Gou, the penultimate DJ, finished her set. Out of Cox’s eyeline rolled a sea of ravers who were, on aggregate, wasted. Nearly 10,000 people had streamed through the depot’s giant doors that evening. Now, with 90 minutes before closing time, more than half that number pressed together to watch whatever Cox was about to do.

Some DJs know exactly what they are going to play, but Cox is not a planner. His method is anti-method. He likes to “feel the room” in the hours and minutes before he begins. He’ll have records on his mind: new stuff, old stuff, maybe an idea of how to finish. Certain sequences are at hand, should the set go one way or another. But, until he has taken the temperature of a crowd, he cannot say for sure what medicine he should prescribe them. The process, as he described it to me, sounded quasi-shamanic.

What, I wondered, did Cox feel in this room? The worst strictures of the pandemic had only recently loosened. The novelty of a mask-free night out with thousands of strangers remained fresh. Sweat dripped from the girders and plastic crunched underfoot. Dazed and forlorn people wandered at the back of hall, as if they’d lost their mothers. Young men with muscles were stripped to the waist. Women in lurid cycling shorts, sports bras, and angular sunglasses held hands in the middle of the crowd, emitting radiant smiles. One guy, pressed against the front railings, looked as if he’d like to drive a tank through a prison wall. The atmosphere was friendly, but tending towards feral.

Cox hugged Gou when she finished her set, and beamed his gap-toothed smile. Roadies wheeled on his rig: turntables, laptop, mixer. There was, momentarily, no sound from the giant walls of speakers. Cox stood behind his decks, said something loud and indecipherable into the microphone, and began to play a heady brew. Locomotive bass was spliced with rave-y synthesiser chords, and a vocal sample that I later discovered was from “Old School” — a track on 2Pac’s Me Against the World album. The crowd, responding both to Cox’s celebrity and to the music itself, went bananas.

A few weeks before Cox played the warehouse, he and I spent a couple of hours together in a recording studio in the incongruously twee setting of a Cheshire market town. We could have spent a couple of days. Cox is 59 years old. He’s a vivid, fast, candid talker, with hundreds of stories from four decades of working in dance music, and he laughs with his whole body. He is also a one-man rebuttal to the idea that DJs are not artists because they play other people’s records. Listen to Cox describe his deep love and encyclopaedic knowledge of dozens of genres, his legerdemain for blending disparate moments in the history of electronic music, his dazzling ability to discern what a crowd might need at any given moment, and his way of introducing a sound so that — in his words — “it plasters you to the bloody wall” and leaves you in no doubt: he is no mere projectionist, he’s the movie.

Cox’s mother and father came to England from Barbados. She was a midwife, and he worked on the buses. Cox grew up in Carshalton, in south London, with his two sisters. (Cox now lives between houses in Melbourne and Brighton, but his vowels have never left the south circular.) There weren’t many other black families in Carshalton in the 1960s and ’70s. Cox remembers being racially abused as a child. He wasn’t particularly hurt by the name-calling, and he recalls that it reflected the atmosphere at the time: an active National Front; Eddie Booth on Love Thy Neighbour calling black people “Sambos”. He left school as soon as he could.

Music lit him up. His parents owned a collection of Soul 45s. Aretha Franklin was a favourite. Cox loved playing them at family parties. He brought a turntable and a speaker into primary school and spun his dad’s 45s for his friends at lunchtime. At 10, when he started getting pocket money, he spent it at the record shop. He supported his vinyl habit by working every odd job he could: cutting grass, decorating, whatever. By 14 — he was a big teen — he was sneaking into nightclubs, where it used to drive him crazy that the DJs talked over the music.

By 16, he owned his own mobile disco, mostly playing funk and soul, but he made money as a scaffolder and painter. At 17, he was sent to prison for joyriding. He spent his 18th birthday serving a short sentence at HM Prison Blantyre House in Kent.

Many of these details are included in Cox’s autobiography, Oh yes, oh yes!. It’s not a dazzling work of literature, but, reading it, I realised how little I knew of Cox’s story. (Superstar DJs occupy a strange position: you may have listened to them thousands of times, and recognise their faces instantly, but most are not celebrities in the traditional sense, and their lives are not public property.) The book’s description of the period that followed Cox’s spell in prison until the birth of acid house in the late 1980s is thrilling. To compress a complicated story: Cox was both witness to and participant in the dance-music explosion of the time. He always wanted to DJ, but felt he had to work harder for his opportunities than white kids. Cox told me he was the victim of racism, both conscious and unconscious: “If there was a white person and a black person going for a job at a club, the white person would get it — and it wouldn’t be because they were better than me… Their face fit a narrative.”

Cox decided to make himself indispensable. He graduated from his mobile disco and bought a nightclub-ready sound system of his own, which he hired out to other DJs. In the mid-1980s, Cox’s equipment was in high demand. Soon, he met DJs like Nicky Holloway, Danny Rampling, Johnny Walker, and Paul Oakenfold. These four would go on a “lads’ holiday” to Ibiza in 1987, and return — having experienced ecstasy, and nights at Amnesia with the Argentinian DJ Alfredo — as evangelists for a new sound called “Balearic” house music. Cox was invited on that holiday, but couldn’t afford the plane fare. He experienced the Balearic moment in London, when he was invited to play at the new club nights that emerged in the wake of the Ibiza epiphany: Project, and Shoom. Cox remembers Alfredo being invited to DJ at Project in Streatham. Cox was in a crowd of glassy-eyed fellow believers that night, and thought “it was like watching the future unfold in front of my eyes”.

Cox, by now living in Brighton, launched himself headlong into the chaos that followed: illegal raves, dodging the police, annoying suburban England. He was still primarily known for his sound system, but he found more and more work as a DJ. In the late 1980s, he was, in his words, “the warm-up to the warm-up” on most bills, but he began to find an audience in the post-club rave nights that began at three or four in the morning on the south coast. At about 10am at a rave called “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, in front of a crowd of flagging dancers, he became the first DJ to use three decks simultaneously. He played two copies of “French Kiss” by Lil Louis and mixed them in with Doug Lazy’s “Let it Roll”. The sound, as Cox recalls, was “fatter than I had imagined it”, and reinvigorated the crowd as if with a cattle-prod. His girlfriend and manager at the time handed out his business card to promoters who were listening. Cox became known as the “Three-Deck Wizard”, and his stock rose vertiginously.

In the warehouse, Cox was nearly an hour into his set, lolling to the beat in trademark fashion, swapping his weight from foot to foot. The venue was still packed. I walked downstairs from the stage, into the crowd. Out of nowhere came a loop of a song that caused a rush of memories. A female vocalist delivered the same line over and over, “every… wakes up early”. It was followed by a familiar burst of piano chords. I soon located the memory, and the sample. It was from “Gypsy Woman (She’s Homeless)” by Crystal Waters, a song that had been popular in 1991. (The lovely refrain: “She’s just like you and me, but she’s homeless.”) Later, I discovered that “Gypsy Woman” had been reworked in 2020 by an outfit called Mr Belt & Wezol. It was that version that Cox was playing. I looked around me. Most of the people in the room weren’t alive in 1991. And yet they still greeted the chords of “Gypsy Woman” like an old friend.

When we met, Cox said he wasn’t in the business of only playing classics. Any resident DJ at any club could do that. He saw his job as a showcase for new music. Producers and artists sent him tracks, and he tested them at live events. The Warehouse was one of his first live shows since the beginning of the pandemic, and he had, in his words, “18 months of music that hasn’t seen the dancefloor, that is bloody awesome.” For his 90-minute set at the Warehouse, he had, he thought, 10 hours’ worth of possible music to play, which the public had never encountered.

“If people are dancing to something they’ve never heard before, that’s an experience,” Cox said. “A crowd wants to be fed. So, it’s maybe five per cent what they know, 10 per cent classics, and the rest is all new…”

Listen to enough Carl Cox sets, and you notice not just this division of fresh and worn, unseen and seen, but also the sheer variety of the music he plays. In many people’s heads, Cox is a techno DJ. (Techno, in the simplest terms, is harder and slightly faster than house, with four strong beats in a bar, and often no vocals.) Cox told me, “I’ll always fly the flag for techno, real underground techno”, but his tastes are oceanic. His favourite album is Songs in the Key of Life by Stevie Wonder. He sometimes likes to play calypso. Kraftwerk knock him over.

Between 2001 and 2016, Carl Cox had a weekly residency at Space, the now-shuttered Ibiza nightclub. Perhaps the best example of Cox’s catholic approach is the final set he ever played at Space. He DJ-ed for nine hours straight, without pause, and concluded with “The End” by The Doors. If you have the time, watch the set on YouTube. It’s the record of a master at work, and a profoundly impressive display of skill and fortitude — not to mention bladder control — for a big man in his mid-fifties. Cox was shaking and close to tears when he brought the music down. He knew that something was ending that could not be replaced. Cox says he will never assume another residency in Ibiza. The island has changed. There are too many VIP tables, too much segregation based on wealth. There are still Ibizan clubs he loves, which hew to a more egalitarian spirit, and where he would happily play one-off gigs. But Space had its own magic: “It was just about the floor, and how you interact with people; didn’t matter if you was a billionaire, or you was a fisherman.”

I asked Cox about the final set at Space, and what it meant to him.

“That night, I moved through a journey of music,” he told me. “It had nothing to do with techno. It was everything about a DJ playing a selection of music for that evening. If I’d played techno for nine hours…” Here, he begins to shake with laughter; I suggest people’s hearts might have exploded. “Yeah! I mean, it would have been insular, it would have been selfish to do that. I love sharing my love of music. So whatever moves me, hopefully moves you.”

Cox is well paid. the Warehouse Project would not share details of their arrangement with Cox, but others who work in the live-music business suggested that his fee might have been £50,000 for the 90-minute set. Cox’s name sells tickets, and the Warehouse had many tickets to sell. The pandemic had nixed Cox’s live shows for 18 months, but he continued to produce music in his studio in Melbourne, where he spends much of his time. Moreover, now that the world was re-opening, he had opportunities to make large sums of money playing live sets to huge crowds, seemingly as often as he needed to.

When I spoke to Cox, however, I was struck by what his career had cost him. In Oh yes, oh yes!, he alludes to the life of a travelling DJ in the late 1980s and early ’90s being “not great for the relationship” with his girlfriend at the time. But other than that, his private life is a closed book. When we met, he told me that he’d been married once, and that the marriage had ended more than 25 years earlier, and that he’d been “nearly-married twice after that”. Relationships were hard, and his lifestyle was partly to blame.

“My wife — that was my girl,” he says. “There wasn’t anyone else. But she felt like a spare part in my world. It was really playing on her mind.” Had he ever wanted children? “I wanted to find the right person to have kids with, and I didn’t want to be a father who was always buggering off every two minutes… But then, time’s passing.”

I sensed a note of regret, but Cox said he felt none. “I think I’ve come to a point in my life where I thought, ‘If I’ve been put on Earth in the way that I was, then this is what I wanted to become’. I can deliver you the best music you’ll hear from an individual. That’s been my calling.” He laughs, aware that he sounds pompous. But he’s serious. “I’m like a techno-evangelist, spreading the love of the kick-drum to the world.”

On New Year’s Eve, 1999, Cox played twice. The first show was in Sydney, where he saw the new millennium in. He then boarded a plane, and flew back to 1999, where he played another set in Hawaii. His life is full of such incidents. He DJ-ed to around a million people at Love Parade in Berlin, in 1998. (A million people!) Cox recounts such tales with a winning bafflement. (“I never thought I’d hit the high-high heights, honestly.”) But it’s not these achievements that feature most prominently in his retelling.

If you ask Cox which moments have been most meaningful to him, he will tell you about the small clubs he’s played, the dense hours when the dancers and the DJs were matched as perfectly as the records — nights that were unrecordable, because you were either there, or you weren’t. He’ll tell you about Womb, a 1,000-person-capacity club in Tokyo, where he shared a bill with the American DJ Seth Troxler, and about how the music was full of riot and variety. Troxler played Prince, “and loads of weird and wonderful things… Amazing, great night. Great club. Proper underground.”

Cox is nearly old enough for his free bus pass. Most of his contemporaries have stopped playing live shows, but Cox’s schedule remains manic. He now gets exhausted by the travel. When he contracted Covid recently, it knocked him out for a month. He’s also got many other interests, including a motorsport team that he owns and loves. He could quite easily just stay in his studio and make new music, never play another gig, and live handsomely. And yet, he’s still on the road. When I ask him why, he talks about Womb, the feeling that he had after the show, and his regret that there were too many clubs to play, and not enough time.

“I didn’t go back to Womb for five years after that night,” Cox said. “Five years! So if I don’t do these events now, I don’t know when I’ll ever do them.”

There were 10 minutes left at the Warehouse. Barring a few exceptions, the ravers in the crowd had kept their phones in their pockets. It wasn’t a set that lent itself to video capture. The music was too propulsive. People were just trying to keep up. But shortly before 3am, the old man behind the decks introduced “Born Slippy”, by Underworld — the track that Trainspotting made famous. I have heard those opening chords thousands of times, but they have lost none of their power. Cox was perspiring heavily and singing along. The crowd was bathed in a blood-red light. A hundred camera flashes now shone above swaying heads. When the drums entered, Cox punched both of his hands forward into the air.

The beat was both a strike and its measure; the kick and its bruise. The thuds arrived faster than twice a second. Each one marked time, and advanced it. The ravers were closer to the moment when they’d disperse into a cold night, and the dread of the following morning. Cox was closer to the moment when he’d receive their acclaim, wipe sweat from his forehead, then slip off to a car, and a hotel bed, and an aeroplane, and more shows in the days to come. Who knew when he’d be back? So many things to see and do, went the song.