When Mummies Were the Life of the Party

Palace model with figures, 1440–1665. Peru. Chimú. Wood, cotton, and shell; L. 19 1/8 in. (48.5 cm), W. 15 15/16 in. (40.5 cm), H. 14 3/8 in. (36.5 cm). Museo Huacas de Moche, Trujillo, Peru, Ministerio de Cultura - Peru

«In the twenty-first century, there is usually a sharp distinction made between the worlds of the dead and the living, with cemeteries now located in park-like settings that are removed from city centers and the daily lives of most. Yet if one reaches further back in time, there is a less pronounced division between the living and the dead, especially in the ancient Americas. The recently opened exhibition Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas, on view through September 18, 2016, provides a rare glimpse into relations between the living and the dead, particularly in one remarkable model on loan to the Met from the Museo Huacas de Moche (above).»

This spectacular model provides a view of a ritual taking place in one of the palace courtyards at Chan Chan, a vast pre-Inca city on Peru's north coast, near the modern-day city of Trujillo. Chan Chan was the capital of the Chimú Empire, a polity that flourished from around 1000 to 1470, when the Inca conquered the region. Located on a low plateau above the Pacific Ocean, the city is dominated by ten monumental mud-brick compounds thought to be the palaces of the Chimú rulers, built by succeeding kings.

Left: In this detail of palace model with figures, we are looking through the entrance to one of the palace courtyards, toward the figure of a mummy.

The Chan Chan palaces, also called ciudadelas (citadels), were enclosed by massive perimeter walls, pierced by only a single entrance at the north. The palaces maintained facilities to serve various functions, from administrative to funerary, including large courtyards in which to hold grand ritual celebrations and extensive storage areas that aided the exchange of goods and official gifts. Looted early in the colonial period, the funerary platforms contained in these palaces are thought to have been the resting place of Chimú kings, their retinue, and descendants.

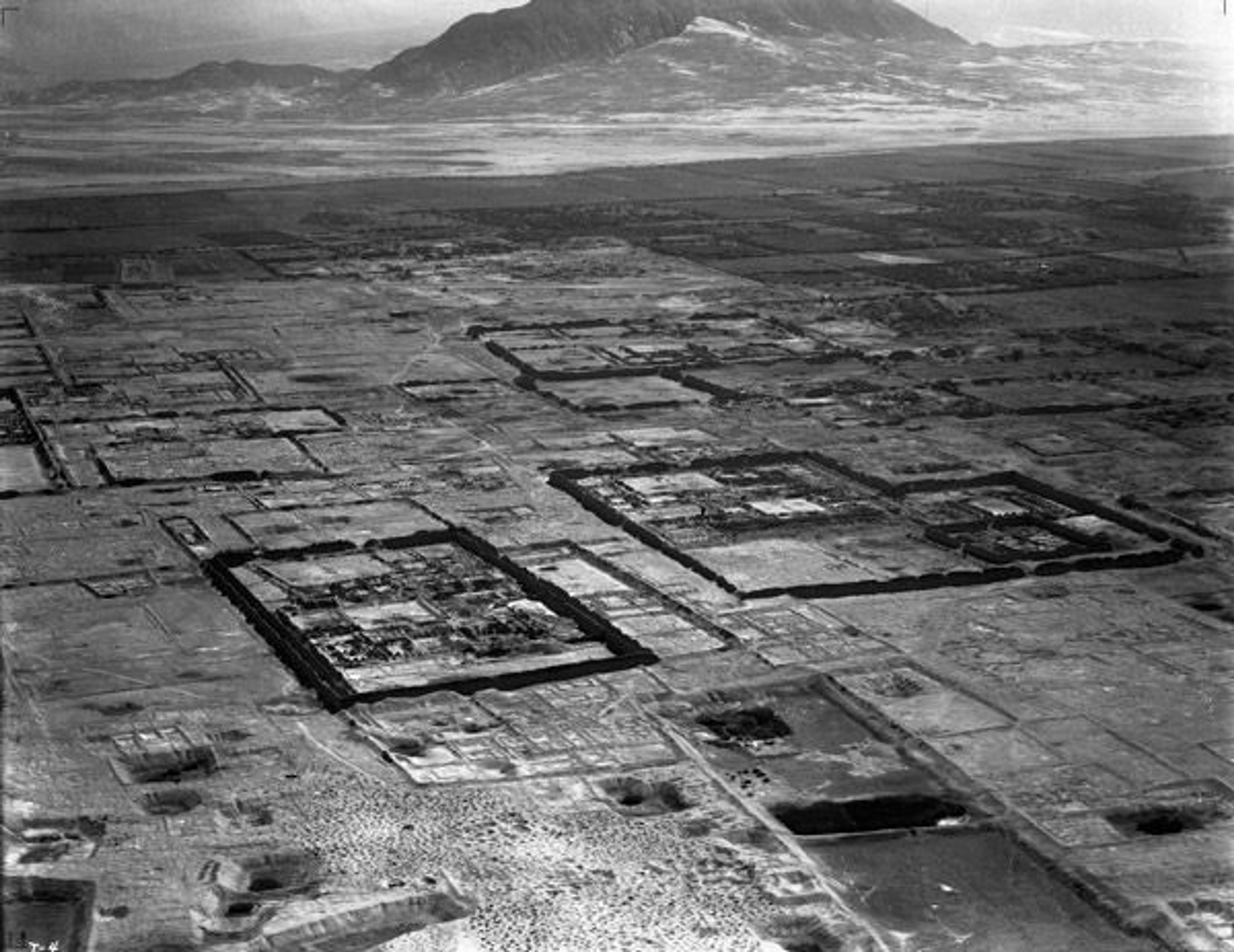

Aerial view of Chan Chan, Peru, 1931. The large enclosures were the palaces of Chimú kings. Photograph by Robert Shippee and George R. Johnson. Image courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History

In 1995 Peruvian archaeologist Santiago Uceda, conservator Ricardo Morales, and their team uncovered this remarkable palace model at Huaca de la Luna, a Moche site some eight miles away from Chan Chan. The heyday of the Moche culture was hundreds of years earlier than the Chimú, from about 200 through 800 A.D. The model, found in a tomb disturbed by looters centuries ago, clearly represents a Chan Chan courtyard, complete with figures sewn to the cloth base. The cast of characters includes courtiers, musicians, and hunchbacks serving chicha (maize beer). Two larger female figures were found in the back of the model, and a larger male figure was found nearby. Carved of wood and covered in a shell mosaic, the mummies were wrapped in coarse tan cloths that resembled funerary shrouds, and the traces of yellow-tan pigment on their faces may represent gold funerary masks. Among the tiny offerings to the mummies—which include baskets and boxes—is a small wood model.

The female mummy figure shown at the top left of the photograph below may be an out-of-towner: the shape of her ears is different from the standard Chimú-style ear ornaments seen on her companions. The distinctive shape of her ear ornaments suggests she is from Lambayeque, a region to the north of Chan Chan.

Detail of the palace model mummies. Photograph by Edi Hirose

This scene may represent a funerary ceremony or a later ritual in which the mummies, revered as ancestors, were honored. The royal dead were not buried during the Inca period, but were instead kept around and periodically celebrated by their descendants. Inca mummies were maintained in palatial accommodations, given new garments on occasion, and brought out to be honored at feasts and other celebrations. As anthropologist Frank Salomon has noted, a mummy "was not at the end of his career but at the beginning of candidacy for ancestral greatness." Mummies could become the focal point for mobilizing an extended kin group into advantageous social and economic positions. Far from relegating your dead to distant and unvisited areas, in the ancient Andes you wanted them around: they were your tangible connection not just to family and community, but to power and the future.

The radiocarbon date of this model—falling somewhere in the range of 1440 and 1665—adds a poignant twist to our understanding of this work. Although only a two-hundred-year span, those two hundred years encompass the late period of the Chimú Empire, the Inca occupation of the north coast, and even the early years of the Spanish viceroyalty (Spaniards arrived in Peru in 1527). The fact that this model was found not at Chan Chan, but at a far older site—one that had been probably long abandoned—suggests that Chan Chan itself had become unsafe for traditional practices, perhaps during a period of foreign occupation, be it Inca or Spanish.

This model was thus interred in a venerated place, out of view of the new rulers. Was it a stand-in for, or a means of remembering, key rituals once held in the great city itself? Or was it, in itself, an offering to the ever-present dead? This model, and others in Design for Eternity, remind us of the deep interpenetrations of the living and the dead in the ancient Andes, as revealed in some of the most complex and intriguing works known from the ancient Americas.

Additional Reading

Pillsbury, Joanne, Patricia Sarro, James Doyle, and Juliet Wiersema. Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Salomon, Frank. "'The Beautiful Grandparents': Andean Ancestor Shrines and Mortuary Ritual as Seen Through Colonial Records." In Tombs for the Living: Andean Mortuary Practices; A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 12th and 13th October 1991, edited by Tom D. Dillehay, 315–353. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1995.

Uceda, Santiago. "Esculturas en miniature y una maqueta en madera: El culto a los muertos y a los ancestros en la época Chimú." Beiträge zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Archäologie 19 (1999).

Related Link

Design for Eternity: Architectural Models from the Ancient Americas, on view October 26, 2015–September 18, 2016

Joanne Pillsbury

Joanne Pillsbury, Andrall E. Pearson Curator of Ancient American Art, is a specialist in the art and archaeology of the Precolumbian Americas. Pillsbury earned her PhD from Columbia University. She was previously Associate Director of the Getty Research Institute and Director of Precolumbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks. She is the author, editor, or co-editor of numerous publications, including the three-volume Guide to Documentary Sources for Andean Studies, 1530–1900 (2008), the Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Award recipient Ancient Maya Art at Dumbarton Oaks (2012), and Past Presented: Archaeological Illustration and the Ancient Americas (2012), which was awarded the Association for Latin American Art Book Award.