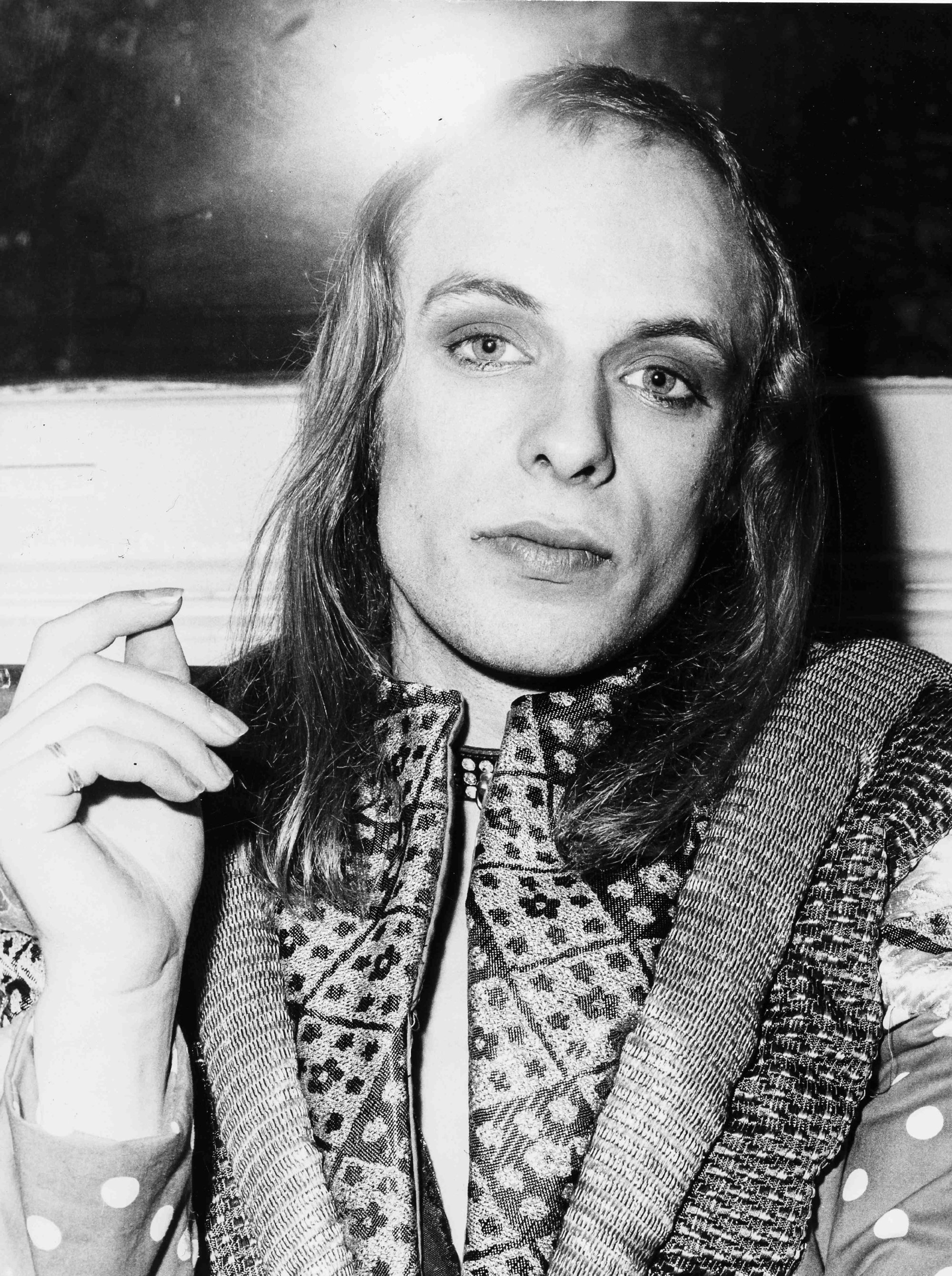

Profile | Brian Eno, musician and producer, on AI-driven documentary Eno and why he doesn’t trust Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg with the technology

- Brian Eno redefined pop working with Roxy Music, David Bowie, Talking Heads, Devo and U2. Now a film about him, Eno, is redefining the documentary

- Eno uses generative AI to produce a different version of the film each time it is shown; the musician and producer talks about the power of AI and its dangers

Part practical problem-solver and part esoteric theoretician, Brian Eno has been involved as a musician and producer on some of the most influential music of the past 50 years, a daunting list of collaborators that redefined pop: Roxy Music, David Bowie, Talking Heads, Devo and U2.

As a solo artist, Eno pioneered the genre of ambient music. He has also extended his work into the visual arts, creating installation pieces.

A new documentary, Eno, directed by Gary Hustwit and recently premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, is an unusual portrait of an artist – the first on its subject.

The project uses a custom-built generative artificial intelligence engine that selects footage and changes edits so the film is different every time it is shown.

“The generative approach was something that was really organic to what he’s done,” says Hustwit on the pairing of subject and form. “He’s been very much an early adopter [of] new technology and ways to integrate it into the creative process. So approaching a movie about him that way made sense.”

Eno says the generative aspect was already part of the film project when he got involved, and a key part for him. “[That’s] because I so despise [films] about artists. They’re always rubbish, in my opinion,” he says.

I’ve resisted ever having a documentary made before, because I just can’t bear most of them

“Nearly all documentaries about artists are so awful because they always take this line. And you think: who decided this was the particular view you should take of that person’s life?

“And of course if it’s about rock musicians, it’s always glamorous and full of fascinating and glitzy things. And I think I know a lot of musicians and I know what their lives are like, and they aren’t generally like that.

“So that’s sort of why I’ve resisted ever having a documentary made before, because I just can’t bear most of them.”

He says creating a generative piece where it will be different every time sounds like a better approach. “Which is, of course, how it is in memory as well. It’s only if you keep a diary regularly, which I do, that you realise how fallible your memory is,” says the 75-year-old Eno.

“You have a memory of a time in your life and then you look back to the diary and you realise you had a completely different experience from what you later imagined you were having.”

‘People didn’t know what to think’: New York street art pioneer’s dark works

The documentary draws from some 500 hours of footage from Eno’s own archives, along with original interviews with the artist himself. Hustwit worked with artist and technologist Brendan Dawes in creating the engine that would generate the film from what was fed into it.

Certain scenes could be pinned to arrive during specific sections, while an overall shape to the film could be maintained even as the order and selection of material would change each time a new version is generated.

The filmmakers do maintain an element of control in the creation of the film – Maya Tippett and Marley McDonald are credited as editors – and watching it feels less channel-flippingly random than you might expect.

A section on Eno’s time with Roxy Music comes at minute 10 or at minute 30 and a viewer is then left to process that information within the larger story accordingly. Inevitably, something will feel missing or left out.

I was just getting bored with the form of cinema and wondering why it couldn’t be more like music, more performative

For Sundance, Hustwit is creating different files for each of the film’s screenings. New footage will be added to the engine even after the premiere, so the documentary will continue to evolve.

As a result, people at different screenings are going to get different versions of the musician’s story and no one will receive the definitive Brian Eno bio.

“And I’m very glad they won’t,” he says. “I don’t want there to be a definitive one. If they act as though they’re definitive, they’re always disappointing.

“There’s always something that got missed that you thought was important or something else that got overemphasised that you didn’t think was very important.”

Hustwit and Eno first collaborated when Eno composed music for Hustwit’s 2018 profile Rams, about the industrial designer Dieter Rams. Around that same time, Hustwit was looking for ways to rethink how to make movies.

“I was just getting bored with the form of cinema and wondering why it couldn’t be more like music, more performative, like every time you pressed play, I would be surprised along with the rest of the audience about what was on the screen,” says Hustwit.

“After meeting Brian and working with him, seeing how he’s using generative technology too, it just seemed to make sense.”

The only thing that really worries me about AI is who owns it. And if it’s in the hand of Silicon Valley frat boys, I’m seriously troubled

For fans curious how many times they would have to watch the movie to see all the possible footage, they may be watching for quite some time.

“The answer is, I don’t know,” says Hustwit, “which is kind of the beauty of the whole generative approach.”

However, the use of generative AI in creative endeavours has also become a concern for some within the industry, especially among writers and actors who went on strike last year in Hollywood.

“The only thing that really worries me about AI is who owns it,” says Eno. “And if it’s in the hand of Silicon Valley frat boys, I’m seriously troubled. If it’s in the hands of people like [Mark] Zuckerberg and [Elon] Musk and all that other group of people, then I think we’re in trouble because I don’t trust them to make the momentous decisions that they’re being called upon to make.

“In a way, the mistake is a social one. We should not have allowed a situation where those very big decisions, which will affect all of our futures quite a lot, are in the hands of a very small number of completely unelected people.”

“I didn’t vote for Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk. I admire them in many ways and think they must be very clever guys. But to find that our societies are being pretty much run by their particular preferences and prejudices is worrying, I think.”

He believes any technology should be used for the greater good and not just for the few individuals who are only concerned with profits: “As long as the thing is connected to the profit motive – the profit not of society but of the individuals who own these platforms – then it doesn’t work for me.”

In Eno, there’s a bit of interview footage with David Bowie and he says, “I’m not quite sure what it is that Brian does”. How does the producer feel that his contribution and work can remain abstract even to his closest collaborators?

“And to me. I always say to people: chemistry is an important model for this. You know, steel is only iron with 2 per cent of carbon added. It appears you just add 2 per cent of this other element, the carbon, and suddenly you’ve got something that behaves entirely differently,” Eno explains.

“So sometimes it’s quite a light touch on something that transforms it into something else.”

“And sometimes it’s hard to remember in the making of something where those moments of significant change occurred, because they might not have been very exceptional-looking at the time. It might have been somebody saying, ‘Shall we stop for 10 minutes?’

“Sometimes that’s a very important creative decision because when everybody comes back 10 minutes later, they’re in a different mind and suddenly things fall into place differently.”

Paris names a street after David Bowie, celebrating music icon’s legacy

So sometimes his contribution might have been as minimal as that, just saying, “Shall we stop for a few minutes?” he says.

“Sometimes that kind of shock to the system creates something new. And then, of course, other times I work like a normal musician. I say, ‘Why don’t we have a G major instead of that B minor’ or whatever.

“In fact, I nearly always say that, ‘Why don’t we have a major instead of a minor’? It’s part of my destroy-minor-chords crusade that has been going on for 50 years or so.”

Today Eno says he cannot imagine what it would be like to retire.

“And it’s not a heroic mission or anything. I don’t get up thinking I should do something important today. I get up thinking, gosh, a new day, what can I do? What do I want to finish? What do I want to start? So I guess I’m resisting getting old.”