Just up from the Place de la République in Paris, where there are still candles, bouquets of flowers and a steel fence in front of the cafe hit during November’s terror attacks, there is a white door stencilled with red letters that read “ORLAN”.

Inside the two-storey building, the walls are lined with bubble wrapped self-portraits. A 3D-printed skull sits on a table; a recent copy of Charlie Hebdo lies on a paper-strewn desk; and a giant fern stands beside a wheel covered in blue Christmas lights. ORLAN’s studio is a jungle.

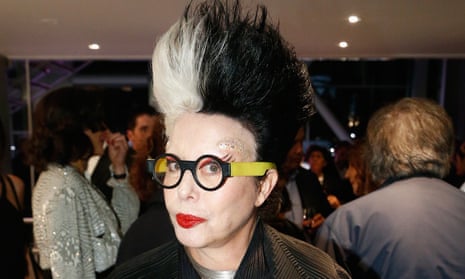

“It’s a casino,” the artist corrects me, her trademark black and white hair standing on end, gleaming subdermal implants tucked above her round owl-like spectacles. “This studio is too small,” she says, rolling her eyes.

ORLAN has been making art for half a century, but her work is soon to return to the limelight as part of the Botticelli Reimagined exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. She also performs alongside art rockers Chicks on Speed at the Volksbühne in Berlin later this month and opens a career retrospective at the Sungkok Art Museum in Seoul in June.

She is 69 but doesn’t look it. A plastic surgery pioneer, she has had nine operations in the name of her art. And it’s not the only thing she has modified. Born Mireille Porte in Saint-Étienne in 1947, she changed her name when she was 15. “I’m like Raphael or Cézanne, it’s my artistic name,” she says. “I have changed my name on my front door, my bank card and my medical card.” But not on her passport, she says, where it’s impossible to have only one name. Can I see it? ORLAN shakes her head. “You’re not the police.”

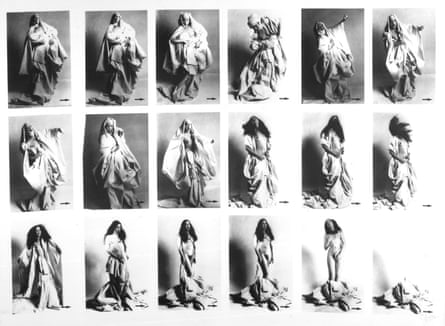

The V&A exhibition will showcase a number of her early works including Incidental Strip-tease Using Sheets from 1974-75. This sequential black and white photo series shows the artist stripping off, removing a set of sperm-covered wedding sheets and posing as Venus from Botticelli’s 15th-century masterpiece. “When a woman strips,” she says, “she will never be completely naked. There are so many prejudices and stereotypes still on her.”

ORLAN puts clothes on in the name of art, too. In 1971, she dressed in baroque garments, baptised herself as Saint-Orlan, charged gallery-goers for kisses with tongue, and gussied herself up as an antichrist superstar with one nipple exposed. Two decades later, in the The Reincarnation of Saint-Orlan, she dressed as a rainbow-hued harlequin and pranced around a hospital operating theatre. Her nip-and-tucks were broadcast live to art institutions worldwide on a satellite network, which was expensive. “Now we have webcams, it’s easy.”

She stayed awake for all her surgeries, reading philosophical essays like a storyteller until she could no longer talk (the surgeon worked for free, she says, in exchange for the art). Flicking through a colour catalogue of photographs, she is taken back to when she lay on the operating table with dotted lines covering her untouched face. “I didn’t have surgeries to be beautiful but really for art, to project new images of beauty,” she explains. “The real goal was to take off the mask you were born with and reinvent it.”

Photograph: Sipa Press/REX/Shutterstock

Don’t ask if her plastic surgery was designed to make her look like an old masters painting – many have said she has the chin of Botticelli’s Venus, the lips of Boucher’s Europa and the forehead of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, among other classic references. ORLAN rolls her eyes again. “It’s absolutely wrong,” she says, sitting up straight. “All my work is against the standard of beauty.”

Carnal art, as defined by ORLAN, is classical self-portraiture made through today’s technology, with the body as a “modified ready-made”. In contrast to body art, pleasure – not pain – is its focus. “Vive la morphine!” as she writes on her website.

This philosophy has been influential. Just last week, ORLAN reopened her $31.7m (£23m) plagiarism lawsuit against Lady Gaga. She plans to subpoena Gaga’s creative team, fashion director Nicola Formichetti and makeup artist Billy Brasfield, for Gaga’s Born This Way cover art and video, which she argues veer too close to her own work. ORLAN’s New York law team are appealing for 7.5% of album sales from a pop star said to be worth $250m.

Sipping tea, she declines to talk about the lawsuit (last year she told Paris Match she is acting as a spokesperson for other artists), but says of her art: “I am a pioneer and I never make compromises.”

While her recent work has embraced technology – 3D animations, augmented reality and apps – she doesn’t see herself jumping on any trends. “The aim is to be contemporary but with a critical distance when using technology,” she says. “Many times with new tech art, it’s almost only that – showing the tech before the idea.”

Her app, AUGMENT, allows anyone who sees her Peking opera-inspired mask series – whether in a gallery, book, or on screen – to take a virtual selfie with the artist. Scans the work with your smartphone (much like a QR code), and out pops a 3D-animated avatar of ORLAN, performing acrobatics similar to those in a Peking opera performance. “Stage time was denied to women in Beijing in the past,” says ORLAN. “As an artist, I am playing with this.”

Feminism is a line through all her work, she says. Her surgical performances were oddly prompted by an ectopic pregnancy in 1978, which saw her rushed to the emergency room. She would have had an abortion anyway, she insists. In fact, she has had several and calls her outlook on motherhood “radical”.

“The COP21 UN climate change conference spoke about pollution, not about women who give birth and pollute the planet,” she says. “As a mother, you have to stay in the house and you need to have no personal life,” says ORLAN. “You have to stop your development.”

ORLAN was one of only six women artists included in the Centre Pompidou’s 2012 book 100 Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century “I was one of two women artists who were alive, four were dead,” she says, holding up the book in her studio. In art school, 75% of students are women, she says, yet only 6% end up exhibiting. “I don’t understand why. It’s a sickness ... I walked a long way for women.”

Still active after most of her peers have retired, ORLAN has climbed to the top of a competitive art world. Does she have a strong work ethic, or a special talent for business? She laughs, sitting down at her desk to answer emails on a Friday night (replying in all caps, just like her name). “I work all the time. I am very creative but it’s still very difficult – if I were a man, I would be more recognised.”

- Botticelli Reimagined is at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, from 5 March to 3 July

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion