I'm bloody awful at multi-tasking," says Brian Eno as he simultaneously polishes some attractive brown leather boots and talks about, well, anything you like, really. Of course, Eno can multi-task rather well. In fact, if you take a look around his studio in a quiet London mews it would appear he can handle all sorts of things: there are paintings and guitars and keyboards and computers running wonderfully obtuse programs, books, odd collage pieces, analogue reel-to-reel and cassette tapes, vinyl albums and compact discs (the latter are his favourite way to listen to music).

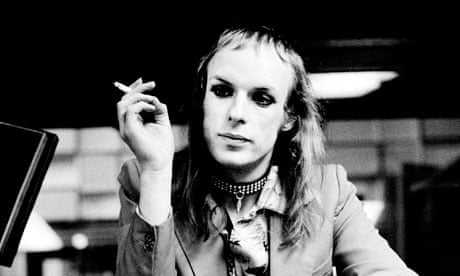

For 40 years now Brian Eno has devoted his life to being anything but a mere musician. His workspace is part-museum, part-laboratory, part playground; the place where he runs riot. Eno has known pop stardom in his time, having worn a feather boa and twiddled a synthesizer's wobbly bits for art-rock legends Roxy Music in their glam 70s heyday on Top Of The Pops (Rolling Stone called Eno's style "happy amateurism"). But that's just one facet. As a scientist, he contributed a chime for a clock that will only ring once every 10,000 years. And as an artist, he once wrote a soundtrack for an experimental video that only "worked" if you turned your TV on its side.

Despite his best efforts however, Eno isn't exactly what you'd call obscure. It's likely you hear more of his work and influence than you realise; not only has he produced three decades' worth of global, radio-eating hits for U2, Coldplay, Talking Heads and David Bowie, he has, by circumventing the norms in song structure and melodic progression, changed the way we hear and process music by others. His influence on dance music is just as great. If you were to remove his records and ideas from the cultural memory then you'd have to take great chunks of acid house, ambient house, jungle, krautrock, dubstep and techno out, too. Multi-tasking is not beyond Brian Eno

Ostensibly, we're here today to talk about Eno's new "spoken word" record, Drums Between The Bells, a collaboration with poet Rick Holland. It's a fine collection, infinitely warm in a post-rave, early-90s, all-back-to-Brian's sort of way. Holland's words are spoken by a variety of different people, including, on the sublime Dreambirds, a woman who works in Eno's local health club.

"I was queuing up and I heard this amazing voice," he says, tucking a brush into the polish. "So I asked her to come back to the studio and read a little."

Did you have to assure her you weren't, you know, an oddball?

"It's all right, she knew me!" he laughs. Eno says this new record is about noticing "moments of energy between music and a voice and trying to make more of them". It's an idea he's become more and more involved with having largely lost interest in the idea that singer should be at the centre of music and that pop music itself is somehow autobiographical.

"It's insane that since the Beatles and Dylan it's assumed that all musicians should do everything themselves," he says, "It's that ridiculous, teenage idea that when Mick Jagger sings he's telling you something about his own life. It's so arrogant to think that people would want to know about it anyway! This is my problem with Tracey Emin; who fucking cares?

"I never wanted to write the sort of song that said, 'Look at how abnormal and crazy and out there I am, man!'" Eno laughs. "Someone like Bowie never wrote those sorts of songs. People like Frank Zappa and Bryan Ferry knew we could pick and choose from the history of music, stick things together looking for friction and energy. They were more like playwrights; they invented characters and wrote a life around them. Bowie played a double game as well as he appeared to live it, too. He played with the form and the expectations brilliantly."

While that dismissal may sound jaded, Eno is not without enthusiasm. Far from it. On one of the shelves in the studio sits a large pine box that holds the six-CD set Goodbye Babylon, a collection of rare, vintage religious music recorded between 1902 and 1960. Eno says it's this very collection that has recently reignited his love for popular music all over again.

"It's just bursting with incredible ideas," he says, "all these amazing ways of singing. I don't know what these people are doing, I don't know how they got to this music; it makes me think, 'What did they think they were doing? Is it rules and principles, or is it pure pleasure?' That's an exciting idea."

If there appears to be a thread apparent in Eno's current taste – one of conflict or contrast – it apparently applies to his interest in current music, too. "Sometimes I can't listen to pop music for a long time," he says. "Then other times I think, 'Christ! It's terrifying how much is going on!' I'm fascinated by musicians who don't completely understand their territory; that's when you do your best work."

One recent CD had a track on which Eno was excited by in the sense it was "nearly brilliant" but just missed something. He found out later it was a song from Radiohead's King Of Limbs.

"They hadn't quite exploited all the drama in the mix," Eno says. "As a listener there was an opportunity missed. But it's such a good record …"

'Burial is so curiously clumsy you can't help but be moved. It's so un-Hollywood and the rhythms are so un-danceable'

Recently asked to choose some new music for a BBC radio show, he was caught between wanting to introduce to people things they've not heard and might like, but also having an aversion to being wilfully obscure.

"I'd like people who hear it to think, 'He's a bit of a twat but he knows a tune …'" We go on to talk about Toronto's Owen Pallett (he of Final Fantasy fame) and how his song Keep The Dog Quiet "starts on the worst possible note he could sing; it's like a mistake, but it's fantastic …" and Eno reveals he likes dubstep more in principle than in fact.

"I love its completely confident embrace of all known recording technologies," he says. "And I love how it's not all horrible and computery, but it's just not a music I very often have reason to play."

So, you enjoy a quick spot of the old womp-womp then move on?

"Exactly!" he says. "Then perhaps some Joni Mitchell. I do like Burial, he's so curiously clumsy you can't help but be moved. It's so un-Hollywood and the rhythms are so un-danceable."

It is, I suggest, dance music you can't dance to.

"And that," he laughs, putting the finished boots on the floor in front of him, "is the very thing that is so very appealing about it. I love the Velvet Underground and they had a drummer (Mo Tucker) who couldn't drum."

We move to a bench outside to better enjoy the afternoon sunshine. Across the way a bewhiskered gent is piloting a heavy, royal blue Jaguar. As Eno leans forward to talk to the man I notice the scar on his head. In early 1975, while walking home from a recording studio, Eno was hit by a taxi and nearly killed. A few weeks later, as he slowly recovered at home, a friend brought over an LP of 18th-century harp music. They put the record on then left, but the stereo was so quiet Eno could barely hear the music over the rain on the windows. Tuned out, he realised he heard light and colour and texture as well as sound. So ambient music was born.

At the time, Eno was being launched as a solo artist. His first solo album, 1974's Here Come The Warm Jets, was a full-on, deliciously odd pop record that battled it out in the charts with the Eagles and Isaac Hayes.

"I was interested in sound design," he says, "and there wasn't any competition. Music was becoming like painting; that's why so many art students like me were so comfortable with it. And it was an easy gig, to be honest."

Now Eno occupies the role of Britain's favourite cultural polymath, someone as delighted by an online radio station from New Zealand called Radio Active ("I'm sure there's rather a lot of high-quality ganja involved in the mix") as he is discussing the late experimental British composer Cornelius Cardew's political shift from minarchism to totalitarianism. Frankly, we are lucky to have him.

A taxi arrives to ferry Eno to a radio interview. In 1978, I tell him, the now defunct Musician, Player And Listener magazine described him as "a good, clear-headed producer, a limited instrumentalist, an adequate vocalist, but a less than memorable melodist". How close were they to nailing you? Eno laughs out loud for some considerable time.

"That's very, very funny," he says. "I love the part about being a less than memorable melodist. Well, I've never had any delusions about what I'm good at and, to be fair, they have sort of identified that. But what's different is that 1978 was the era of musicians, while now is the era of producers. Like the 18th and 19th century was about those who understood the great innovation of that time: the orchestra. Today's great innovation is the studio, the recording process and that every piece of music, apart from being a sonic pleasure, is an experiment in social organisation. There is a morality there, a producer tries to make the social unit work, and so the music you make is a statement of belief about how society could work."

He pauses and picks up the shiny leather boots: "It's quite deep really, isn't it?"

Brian Storm: six of Brian's best

HERE COME THE WARM JETS (ISLAND, 1974)

The sound of super-warped glam enlivened by breezily surreal art-pop. Eno succinctly described his debut album as having an "idiot glee" to it.

AMBIENT 1: MUSIC FOR AIRPORT (EG, 1978)

Brilliantly simple and reflective piano and choral pieces designed purely to give you a space to exist in; this is ambient music's Kind Of Blue.

BRIAN ENO & DAVID BYRNE: MY LIFE IN THE BUSH OF GHOSTS (SIRE/POLYDOR, 1981)

Long, elliptical grooves, African and Middle Eastern folk singers and bizarre, ripped-from-the-radio cassette-based ephemera.

SILVER MORNING, from APOLLO ATMOSPHERES AND SOUNDTRACKS (EG, 1983)

Daniel Lanois's country-scented guitar piece has, thanks to Eno, the same weightlessness as the astronauts it celebrated.

HAROLD BUDD: THE PEARL (EG, 1984)

Budd is the master of improvised, minimalist piano, and Eno's production makes this a fantastically textured album of great subtlety and charm.

ANOTHER GREAT DAY ON EARTH (OPAL, 2005)

Twenty-eight years after he last sang, Eno returns with words and melodies to accompany the liquid electronica and sublime ambient-pop. Actually lovely.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion