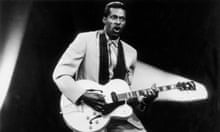

Chuck Berry, who has died aged 90, was rock’n’roll’s first guitar hero and poet. Never wild, but always savvy, Berry helped define the music. His material fused insistent tunes with highly distinctive lyrics that celebrated with deft wit and loving detail the glories of 1950s US teen consumerism.

His first single, Maybellene, began life as “country music”, by which Berry meant country blues, but was revamped on the great postwar Chicago label Chess in 1955. It was not only rock’n’roll but the perfect indicator of just what riches its singer-songwriter would bring to the form. Starting with a race between a Cadillac and a Ford, told from the Ford-owner’s, and therefore the underdog’s, viewpoint, this immeasurably influential debut record featured one of the most famous opening verses in popular music: “As I was motorvatin’ over the hill / I saw Maybellene in a Coupe de Ville ...”

Here, out of nowhere, was the enticing combination of an instantly recognisable, fresh guitar (“just like a-ringin’ the bell,” as he would soon put it), a blow-by-blow narrative, a relish of brand-name detail, and a slyly innocent joy at being so au fait with such detail. These would be the hallmarks of almost all Berry’s best work.

So would the seamless match of words to melodic line. This technical panache was part of his humour. Take the opening lines of Nadine (1964): “As I got on a city bus and found a vacant seat / I thought I saw my future bride walkin’ up the street / I shouted to the driver, ‘Hey conductor! you must / Slow down, I think I see her: please, let me off this bus!’ / ‘Nadine! Honey, is that you? ...” The wonderfully lively, perfect fit of street-talk to music avoids mere automatic chug-a-chug-a-chug, showing off the true poet’s touch as the rhythm enacts the plea that “you must [pause] slow down ...”

Here, right from the outset, was an artist with wit, the very quality supposed to belong only to the music that rock’n’roll displaced. And Berry never paraded cleverness for its own sake but always in energetic celebration of life. The Everly Brothers would master teenage-bedroom angst, but Berry proclaimed the upside of modern adolescence – although he was already 19 by the end of second world war, and turning 30 by the time he began singing about high-school romance.

Berry’s music was, as the critic Tom Zito observed, “not so much black as American”. Yet stories like Maybellene were certainly in the spirit of Stagger Lee and the other speedy superheroes of black folk tradition, while Brown-Eyed Handsome Man (1956) asserted that black was beautiful ahead of its time – the title’s understatement adroitly set against the extravagant wordplay of the verses: “De Milo’s Venus was a beautiful lass / She had the world in the palm of her hand / But she lost both her arms in a wrestling match / To meet a brown-eyed handsome man.”

Berry’s songs ranged far beyond adolescence. Havana Moon (1956) is a vivid drama of lovers’ lost opportunity, as affecting as Brief Encounter, but funky and told in three minutes; You Never Can Tell (1964) smiles at newlyweds, as do “the old folks” inside the song; Memphis, Tennessee (1959) laments the pain of divorce as the narrator sings of his missing six-year-old daughter Marie, last seen “with hurry-home drops on her cheeks that trickled from her eye ...”

This was something Berry knew about. He was born in Saint Louis, Missouri, one of six children of choir-singing parents. “My childhood was not so good,” he said. “My parents were getting divorced.”

His first guitar was a second-hand Spanish acoustic, but by 1952, influenced by the 1940s guitarist Charlie Christian, blues singer Tampa Red and the Nat King Cole trio, he had gone electric and semi-pro, working east St Louis clubs in the pianist Johnnie Johnson’s trio, renamed the Chuck Berry Combo when Chess released Maybellene to instant success.

His guitar-driven classics in the prolific years that followed were the anthems every local group played every weekend ever after. They included Roll Over Beethoven, Too Much Monkey Business, Oh Baby Doll, Rock & Roll Music, Sweet Little Sixteen, Johnny B Goode, Carol, Little Queenie, Back in the USA, Bye Bye Johnny, Come On, No Particular Place to Go, Reelin’ and Rockin’ and The Promised Land.

Through them all, Berry offered a bold and captivating use of cars, planes, highways, refrigerators and skyscrapers, and also the accompanying details: seatbelts, bus conductors, ginger ale and terminal gates. And he brought all this into his love songs. He put love in an everyday metropolis, fast and cluttered, as no one had done before him. In Berry’s cities, real people struggled and fretted and gave vent to ironic perceptions. Berry also specialised in place names, as no one else has done before or since. His songs release the power of romance in each one, flying with relish through a part of the American dream.

In the midst of these hits, Berry was imprisoned. At 18 he had been jailed for three years for petty robbery, and in 1959 held for trying to date a white woman in Mississippi. In 1960, married with four children, he was found guilty of taking a 14-year-old girl across a state line. Berry protested that she only went to the police after he fired her from his nightclub, and that anyway he had thought she was 20. He was jailed again until late 1963. He served his time honing his songwriting, and his records of 1964 were at least as good as the earlier hits.

In 1972 came My Ding-A-Ling, a smutty song wholly lacking Berry’s usual artistry. He topped the charts at last, at the age of 46. By then Berry’s eulogies of Americana (“I’m so glad I’m living in the USA ... Where hamburgers sizzle on an open griddle night and day ... Anything you want they got it right here in the USA”) had long been deeply unfashionable, as the Beatles had noted with their sardonic Back in the USSR.

Yet Berry’s huge influence – out of all proportion to the modest chart placings of his crucial records – remained tangible throughout the 1960s and beyond, both generally and in particular, as upon the Beach Boys (Surfin’ USA), the Beatles (Get Back), the Rolling Stones (Come On was their first single, Maybellene the vocal model for Jagger), Bob Dylan (Too Much Monkey Business engendered Subterranean Homesick Blues) and right on through to rap.

Berry left Chess for Mercury in 1966 but soon came back, and though his 1973 album Bio used John Lennon’s band Elephant’s Memory, the material looked back to pre-rock days. Motorvatin’ was a UK Top 10 album in 1977. Berry continued to perform live, either side of another prison term in 1979 (four months for income tax evasion), famously demanding cash upfront, arriving at the last possible moment, using local backing groups with whom he declined to soundcheck, and often showing truculence on stage.

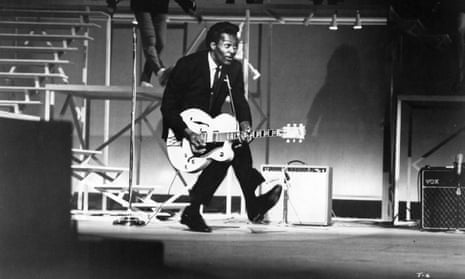

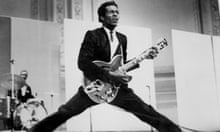

This notoriety misled, as the 1987 documentary film Hail! Hail! Rock’n’Roll! proved. More than 30 years after his film debut in Rock, Rock, Rock!, he was still obliging with his trademark duck walk and coaxing those lazily bent notes from his beautiful scarlet Gibson guitar, his alert grace intact. And some indifferent concerts were the price paid for genuinely spontaneous performance that on other nights yielded moments of magical reinvention and creative musicianship.

His 1987 book Chuck Berry: The Autobiography revealed a man with no need of a ghostwriter, no self-serving whinges and a strong sense of black history.

He continued to age remarkably well, despite recurrent ill-health. Performing in front of 10,000 people at the age of 83 at the 2010 Viva Las Vegas open-air concert, he was lithe, challenging his back-up musicians with a spontaneous reshaping of the pace and delivery of his classic songs, and giving good value to the audience, some of whom were young enough to be his great-grandchildren.

He performed once a month at a restaurant in St Louis, Blueberry Hill, until 2014, the year in which he was awarded the Polar music prize, and intermittently thereafter. Among other honours, he received a Grammy lifetime achievement award in 1984, and a Kennedy Center Honor in 2000.

He is survived by his wife, Themetta “Toddy” Suggs, whom he married in 1948, and four children, Ingrid, Chuck junior, Aloha and Melody.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion