Bernard Sumner (Joy Division): I felt that even though we were expecting this music to come out of thin air, we never, any of us, were interested in the money it might make us. We just wanted to make something that was beautiful to listen to and stirred our emotions. We weren’t interested in a career or any of that. We never planned one single day.

Peter Hook (Joy Division): Ian was the instigator. We used to call him the Spotter.

Ian would be sat there and he’d say: “That sounds good, let’s get some guitar to go with that.” You couldn’t tell what sounded good, but he could, because he was just listening. That made it much quicker, writing songs. Someone was always listening. I can’t explain it, it was pure luck. There’s no rhyme or reason for it. We never honestly considered it, it just came out.

Stephen Morris (Joy Division): Ian was pretty private about what he wrote. I think he talked to Bernard a bit about some of the songs. He was totally different to how he appeared on stage. He was timid, until he’d had two or three Breakers, malt liquor. He’d liven up a bit. The first time I saw Ian being Ian on stage, I couldn’t believe it. The transformation to this frantic windmill.

Deborah Curtis (wife of Ian Curtis): He was so ambitious. He wanted to write a novel, he wanted to write songs. It all seemed to come very easily to him.

With Joy Division it all just came together for him.

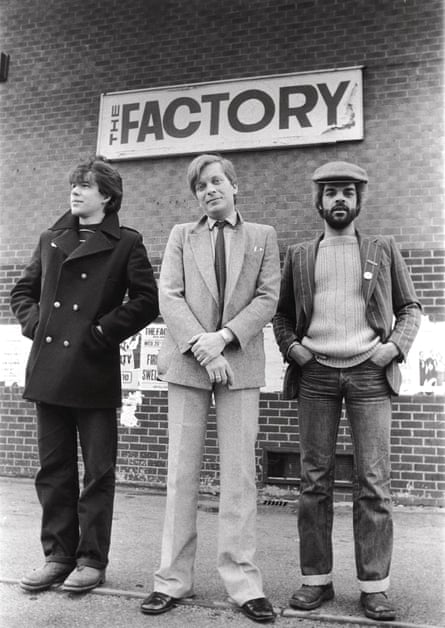

Tony Wilson (presenter, Granada TV; Factory co-founder): I think that psychogeography and the concept of the city was at the centre of situationism in the 50s in France and the degraded city was part of Joy Division’s life: Macclesfield boys, Salford boys, and there is the city – Manchester. The idea of the city is a theme that runs through this whole thing, Manchester being the archetypal modern city.

Bernard Sumner: You were always looking for beauty because it was such an ugly place, whether again on a subconscious level. I mean, I don’t think I saw a tree till I was about nine. I was surrounded by factories and nothing that was pretty, nothing. So it gave you an amazing yearning for things that were beautiful, because you were in a semi-sensory-deprivation situation because you were brought up in this brutal landscape, but then when you did see something or hear something that was beautiful, you would go: “Ooh, new experience” and really appreciate it.

The hills are the escape from it, from the horrible, industrial, dead landscape of Salford and most of Manchester; the sheer contrast between the moors and the industrial filth that surrounded us in the 60s. I remember someone telling me on the way home from school that Salford was considered the biggest slum in Europe, and I couldn’t believe it, because it was where I lived. I read that living in Salford was the equivalent of smoking 70 cigarettes a day.

Peter Hook (Joy Division): I was born in Ordsall, in Salford, and I was raised there for most of my life, apart from a brief three-year stint when I lived in Jamaica for some strange reason. Salford’s special and Manchester isn’t. I’m not proud of it, Salford has a very stubborn and very aggressive reputation, whereas Manchester’s just Manchester. It’s always been a struggle living in Salford. It’s very, very poor, very downtrodden, very industrial.

It’s interesting when Bernard says that Unknown Pleasures came from that, which I suppose it did. I don’t think consciously Bernard and I were struggling to get out of it. I think we were quite happy with our lot, to be honest. But I suppose subconsciously it would have a big effect on you.

Stephen Morris (Joy Division): When I was growing up we used to come to Manchester and go back again. I remember the first time in Manchester, seeing all these end-to-end terraced houses, and then the next time you went there was just a pile of rubble, then the next time you went there was all this building work. Then, by the time you were in your teens, it was this big concrete fortress, quite futuristic at the time.

The College of Music was there, and Oxford Road was futuristic in the 70s. There were grim bits, but compared to Macclesfield it was the bright lights.

Liz Naylor (writer, City Fun fanzine): The city at that time was just overrun by the dispossessed, and I felt extremely dispossessed and disempowered. And it’s the most at home I’ve ever felt living anywhere. Joy Division felt very close to me. They were my first band. I think they were a band that really appealed to outsiders, you know, and girls. I might not have felt like a girl but I was a girl and I was quite vulnerable, and they really connected with me. My thing about Joy Division is they’re an ambient band almost: you don’t see them function as a band, it’s just the noise around where you are.

Richard Boon (Buzzcocks manager): I met Ian Curtis on 10 November 1976 at the Electric Circus [venue], where Buzzcocks, in the tradition of doing it for yourself, had hired the Electric Circus and brought [punk band] Chelsea up from London. I was doing the door. Ian came in talking about having a rubbish time at the Mont de Marsan festival, which had been hyped in the summer as being some legendary French thing which he found ultimately disappointing, but he was obviously coming from the same kind of idiot enthusiasm that we were sharing.

Bernard Sumner: I first met Ian at a gig at the Electric Circus. It might have been the Anarchy tour, it might have been the Clash.

Ian was with another lad called Iain, and they both had donkey jackets, and Ian had ‘HATE’ written on the back of his. I remember liking him.

He seemed pretty nice, but we didn’t talk to him that much. I just remembered him. About a month later, when we decided to try and find a singer, we put an advertisement in Virgin Records in Manchester, which was the way that all groups formed during the punk era.

We put an advertisement in there, and I got loads of headcases ringing me up. Complete maniacs. Then Ian rang up, and I said: “Weren’t you the one I met at that gig, that Clash gig? With the other Iain?” “That’s me,” he said. So I said, “Right, OK, you can be the singer then.” We didn’t even audition him. We asked what sort of music he liked, and it was the same kind of music as us, so we gave him the job. Ian and Debbie were staying at Ian’s mother’s at that stage, near Ayres Road in Moss Side, and me and Hooky went over to see him in person and gave him the job then.

Terry Mason (Joy Division road manager): We vaguely knew him, more on the grunting terms that young men do. The punk situation in Manchester was you basically knew most of the people who went to every gig by sight, you didn’t know what their name was, but you’d [mumbles].

He seemed OK. We got talking to him, he came out with his books of lyrics, and he had a lot of index cards with songs or bits of songs on, and he actually owned equipment: a couple of column speakers and a tiny amp.

It was obvious that this guy was serious. He was prepared for it and he didn’t scare us, so we decided to see if we’d like him. So Ian’s audition as such was we invited him to come out with us one Sunday afternoon, and we went to Ashworth Valley, in Rochdale.

Basically, we spent a couple of hours just acting like kids, throwing bits of wood into streams and jumping over them. On reflection, it wasn’t a bad audition technique. It worked. I’m not sure what Ian thought of it when he went home and told Debbie what he’d been up to.

Peter Hook: Ian was much better educated for things like Can, Kraftwerk, Velvet Underground. I was a big fan of John Cale, because a kid I used to work with in the canteen at the Manchester Ship Canal Company was a mad John Cale fan and he gave me all his LPs. It was Ian that introduced us to Iggy and things like that, because Bernard and I were listening to pop, reggae, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple. Ian didn’t push it on you, he wasn’t pushy with us at all, and he was just great to be with, he completed your education.

Bernard Sumner: He brought a direction. Ian was into the extremities of life.

He wanted to make extreme music, and he wanted to be totally extreme on stage, no half measures. If we were writing a song, he would say: “Let’s make it more manic! It’s too straight, let’s make it more manic!”

Richard Boon: They were in a constant process of forming. We used to visit them in the rehearsal room near the bus depot in Weaste and drink with them afterwards, and they were just trying to get a handle on what they wanted to do. They just wanted to be in a band, which is no mean ambition.

Ian was possessed by burning youth. I wouldn’t go as far as to say he was anything like Arthur Rimbaud, but he was enthused primarily by the Stooges and the Velvets and his own sense of alienation. He was obviously trying to work something out and he could be as laddish and as loutish as the rest of them, but you always sensed he’s making an effort to be a lad, he’s really a little more withdrawn, a little more thoughtful, which just made him charismatic, but he was no saint.

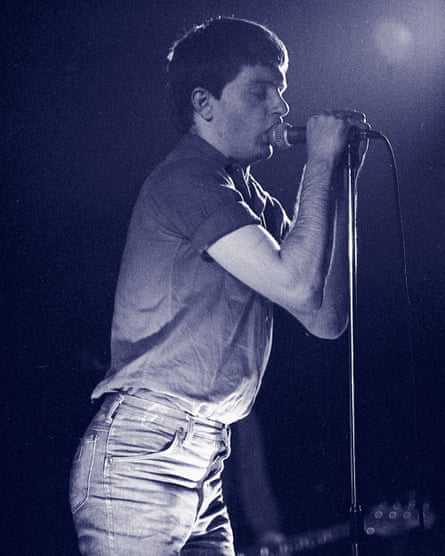

Tony Wilson: Ian’s performance was always electric, but it would suddenly get even more electric. You wouldn’t see Ian about to go off, but you would see Bernard and Hooky and Stephen begin to look at each other on stage, and I began to recognise it from that.

One of the most profound performances was after they’d supported the bloody Stranglers at the Rainbow [venue in Finsbury Park, north London] and then come across to do [the] Moonlight [venue in West Hampstead], which was some crazy idea that we’d had – which I should apologise for because it did set Ian off.

Lindsay Reade (wife of Tony Wilson): The more the gigging got intense, the more the [epileptic] fits were taking place. But this may have a parallel with his private life as well, because the two things were amplifying together in terms of stress. The stress of performing, of being on the road: the demands on his time were getting much bigger with each month or week.

Plus his private life was disintegrating because he’d got the stress of having a baby, plus the fact that his marriage was in pieces and he loved another woman. He was an honourable guy, he didn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings and he wanted to do the best for everybody, so you’ve got two things tearing him apart.

Paul Morley (writer, New Musical Express): The whole point of Ian is that after a while it seems that he was always on the edge of life. There were obviously moments when you just assumed it was part of the choreography, as anarchic as that choreography had become, and then selfishly you enjoyed it because it was an event, it was a happening, it was a thing, and he’d given it. He was really laying his life on the line for this music, and it elevated everything and there seemed to be a kind of sacrifice.

You felt that he was really entering into what Iggy Pop would do – it seemed to be his equivalent of slashing his chest – really giving you something, giving you a heck of a performance. Selfishly you’d deem it a kind of extreme entertainment. At that time there’d be Public Image, there’d be Throbbing Gristle, there’d be Gang of Four: that tearing apart of cliches suddenly seemed to have ideological fervour and purpose, and Joy Division seemed to be part of that.

There was a real reason for this, and it went beyond just fashion and style and music.

Bob Dickinson (writer, New Manchester Review): The thing about Ian was that he was the focal point for the band, and his vocals and his lyrics are incredibly vulnerable. I was always interested in the way that he wanted to use this very strange American accent and pitched his voice very low, and it sounded to me very ethereal, like a character from a film, something that floats in front of you and isn’t quite there.

And at the same time he’s got this charisma. Hooky has charisma, Barney has charisma, the whole band has a joint charisma, but Ian’s charisma was unnerving and unsettling because of the physical things that he did on stage. Once you’d seen him, once he’d done that thing where he shook himself into a frenzy, into a kind of dance that was not a dance, it was a disturbing kind of fit, once he’d done that and you’d seen it, you knew that the next number you saw or the next occasion where you saw them, he was going to take you in that direction. You didn’t know where you were going to end up, you didn’t know what was going to happen to him. It was unsettling to watch him do it, it was thrilling to watch him do it, but you just didn’t know where it was going to take you.

I think that kind of charismatic power was what really captured my attention. It still grabs me when I see them on film, I still find that really unsettling to watch. Every show was a unique journey.

Bernard Sumner: That video for Love Will Tear Us Apart was shot [28 April 1980] just after Ian had tried to kill himself [for the first time], so it was a really trying time for us.

There are some very famous photographs. Anton Corbijn took them. Me and Ian are carrying a flight case, and Ian’s sat down, like this, and he looks quite depressed. He wasn’t normally like that, but that was quite near to the end. We felt: “Well, what can we try to do to cheer him up? We’ll write a couple of songs.” And we wrote In a Lonely Place and Ceremony in a week, we shot the video, but it was all hopeless really.

Tony Wilson: The last conversation we had, which was at the Birmingham gig [2 May 1980], which was the last gig ever, was about how interested I was in his and [A Certain Ratio frontman] Simon Topping’s use of archaic language. Now I can’t quite remember which: there’s a line from A Certain Ratio and a line from Joy Division around that time which interested me.

I think one of them is “When all’s said and done”. It’s an archaic use of language, and that interested me that they both used it.

Peter Hook: The police phoned me up [18 May 1980]. They couldn’t get in touch with Rob [Gretton, [Joy Division manager and Factory co-founder], they couldn’t get in touch with anybody. I was the first one that they told. It was really weird because I was sitting down just about to have me Sunday lunch, me and Iris, and the phone rang. I went on the phone, and they said: “We’re trying to get in touch with Rob Gretton.”

And I said: “He should be at home.” They said: “We phoned him at home, he’s not there.’ I said: “Why, what’s the problem?” And they said: “Oh, I’m sorry to tell you this, but Ian Curtis has committed suicide.”

And I went: “Right, OK.” And they went: “Right, OK. Well, if you speak to Mr Gretton, could you get him to call us?” And I went: “Yeah, right, OK” and put the phone down, and went and sat back and had me dinner. And then Iris said to me: “Who was on the phone, by the way?” And I went: “Oh, Ian’s killed himself” and that was it then, that was the shock of it. It was really weird, horrible, and then everything seems a blur after that. I must have tried to get in touch with Rob, or driven probably to see him – I can’t remember, to be honest.

Deborah Curtis: I think he wanted to be like Jim Morrison, someone who got famous and died. Being in a band was very important, he was very single-minded about it. He’d always said that he didn’t want to live into his 20s, after 25. I think it was the teenage thing. Teenagers like to have something to be miserable about, don’t they? But it changed. He stopped talking about it. I don’t think he forgot about it. I thought he’d grow out of it. And when it got too late really, he wouldn’t talk about it. You couldn’t discuss it with him, you couldn’t find out what was really going on.

When we were kids, lots of people were miserable. But they grew out of it. I think he enjoyed being unhappy. I think he liked to wallow in it.

There were times when we were happy, but they were when we were on our own, when we went out walking or things like that. But I don’t think he liked his friends to know that he was happy. You know that Ian was very charismatic, and he tended to lead people, and people liked to be part of his will, so I don’t think anybody really questioned what he was doing very much. Because he was different, so many people admired him.

Bernard Sumner: I knew why he’d done it. Or I could put my own reason on why I thought he’d done it, why I would have done it. At the time I remember going very silent, not being able to speak very much. Just feeling very down. I think it makes you very hard. I feel now that I’m quite cold, and when I was a child I was very warm. Now I can be quite cold and detached. I can never really make close friendships, just because everything I’ve ever been close to has died.

It just seems a bit callous to do that towards the people that love you. If you’re going to do that, you’ve got to think about your parents and your close ones more than yourself. It seems quite a cruel thing to do, so my heart’s angry but my brain is saying: “Don’t be so judgmental.” It’s hard to get in Ian’s head and think: “What did he think his future was going to be?” He must have had a bleak image of his future, because he was very, very ill, very ill, and those days weren’t these days: the care for it wasn’t as good as it is now.

Stephen Morris: Why did we decide to carry on? Well, we just carried on, we never even thought: “Should we carry on or not carry on?” We went to the funeral, we went to the wake at Palatine Road, so “Monday, see you on Monday then” that was it. To this day we’ve never really sat down and said: “Well, we’re going to do this and we’re going to this and we’re going to do that.” You just start and do it and hope for the best, because that’s the way we are.

This is an edited extract from This Searing Light, the Sun and Everything Else – Joy Division: The Oral History by Jon Savage, published by Faber (£20.99). To order a copy for £17.60 go to guardianbookshop.com or call 0330 333 6846

In the UK, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international suicide helplines can be found at befrienders.org