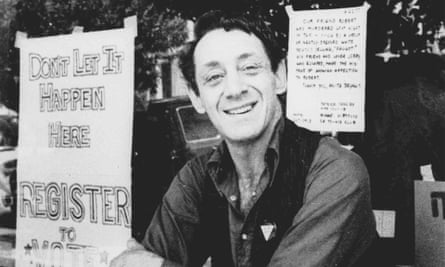

More than 500 LGBTQ politicians hold public office in the US. They are city council members, mayors, members of Congress, state legislators, even governors. Hundreds more have been elected in countries around the world, including four heads of state. But 40 years ago, only a handful of gay men and lesbians had been elected to office. One of them was my friend Harvey Milk.

Harvey was charismatic, funny and something of a father figure to me. He was one of the first people to tell me that I had value as a human being and that I didn’t need to change.

I worked for Harvey as a student intern in San Francisco city hall, earning credit in the political science program at San Francisco State University. I got to work early on 27 November 1978, but Harvey needed to see a file that I had left in my apartment on Castro Street and sent me home to retrieve it. As I left my apartment, I heard someone shout that Mayor George Moscone had been shot. I flagged down a taxi and told the driver to get me back to city hall.

The driver dropped me off on Van Ness Avenue at the western side of city hall. I ran in, seeing the police swarming around the mayor’s office on the other side of the building. The cops frightened me and I ran up the stairs. The Board of Supervisors office was on the second floor and each supervisor had a small office opening to a private hallway that ran parallel to the public hallway. There was a passageway that connected the ornate supervisor’s chambers to the reception area and the hall to the individual offices.

Harvey had given me a key to the passageway and as I let myself in I saw even more police officers running up the stairs. I felt panic in my chest and turned left towards the offices, looking for Harvey when Dianne Feinstein and an assistant rushed past me. Feinstein’s sleeve and hand were streaked with dark red.

I looked down the hallway and saw Harvey’s feet sticking out from Dan White’s office. I recognized his secondhand wingtip shoes immediately.

Then my memory shifts to slow motion.

I float to the door of White’s office and peer in. There is a cop there, on his knees, turning Harvey’s body over. I see his head roll. I see blood, bits of bone, brain tissue. Harvey’s face is a hideous purple. I feel all the air leave my lungs. My brain freezes. I cannot breathe or think or move. He is dead. I have never seen a dead person before.

I struggle to comprehend as my mind begins to understand what my eyes are seeing. The only thing that I can think is that it is over. It is all over. He was my mentor and friend and he is gone. He was our leader and he is gone. It is over.

We are there for hours, trapped in his little office as they bundle up his body. People come in. More cops. We find Harvey’s old cassette player and the taped message he had recorded in anticipation of his assassination.

I’d known of the tape and teased him a bit, “Who do you think you are, Mr Milk? Dr King? Malcolm X? I don’t think you’re important enough to be assassinated.” We press the play button.

And now he is dead and it is all over and we are listening to his voice tell us that he always knew that this is how it would go down.

This is what he expected. This is what he was willing to do. This is what had to happen.

And all I can think, all I can say to myself is, “It’s over. It’s all over.” And then the sun goes down and the people begin to gather.

They come from all over the Bay Area: young and old; black and brown and white; gay and straight; immigrant and native-born; men and women and children of all backgrounds streaming into Castro Street – Harvey’s street – faces wet with tears, hands clutching candles. Hundreds, then thousands, then tens of thousands fill the street and begin the long slow march down Market Street to city hall, a river of candlelight moving in total silence through the center of the city.

There were songs and speeches but I remember none of them. I stood there in Civic Center Plaza in the midst of an ocean of candlelight, in front of the building where Harvey died, in the middle of the city he had come to love and that had come to love him back in equal measure. And now it was all over.

My friends and I walked slowly back to Castro Street. Police cruisers lined Market Street and followed the returning marchers but they kept their distance. Had they been closer we might have heard what they were hearing: over the police radio, the cops were singing.

“Oh Danny Boy, the pipes, the pipes are calling. From glen to glen and down the mountain side … Oh Danny Boy, Oh Danny Boy, I love you so!”

I was wrong. It wasn’t over. It was just beginning.

This piece contains an extract from Cleve Jones’s When We Rise: My Life in the Movement

A memorial for Harvey Milk and George Moscone will take place tonight at 7pm, Harvey Milk Plaza, San Francisco. For other events go to Harvey Milk LGBTQ Democratic Club